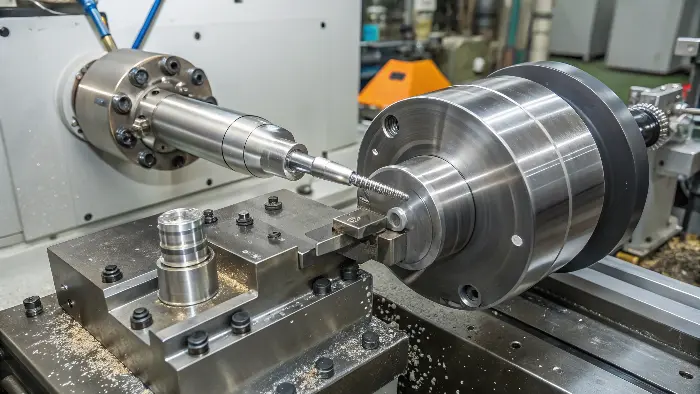

Have you designed the perfect component, only to specify stainless steel and watch the project timeline and costs spiral? You’re not alone. This tough material often introduces unexpected challenges. Understanding why it’s so difficult is the first step to mastering it and keeping your project on track.

Stainless steel is hard to machine because of its high work-hardening rate, low thermal conductivity, and high ductility. These properties cause rapid tool wear, problems with chip control, and extreme heat buildup at the cutting edge. This combination makes achieving tight tolerances and a good surface finish a significant challenge for any machinist.

I’ve seen many engineers struggle with this. They send over a design, and the quote for stainless steel is much higher than for aluminum or mild steel. They often ask me, "Jerry, what’s the deal with stainless?" It’s a great question, and the answer isn’t just one thing. It’s a combination of factors that all work against the cutting tool. Let’s break down the specific reasons behind the difficulty and, more importantly, what we can do about it.

Why is stainless steel difficult to machine?

Your stainless steel parts are wearing out tools faster than you can replace them. This drives up your costs and delays your project timeline significantly. The key is to understand the material’s core properties that actively fight back against the cutting tool, turning a simple cut into a battle.

The main reasons are its high chromium content, which creates a tough, abrasive surface, and its tendency to work-harden. When you try to cut it, the material just ahead of the tool becomes harder instantly. This requires more force and generates more heat, creating a vicious cycle that quickly dulls even the toughest cutting tools.

When I first started in a machine shop, I learned quickly that not all metals are created equal. While aluminum cuts like butter, stainless steel fights you every step of the way. For an engineer like Alex, who needs precision parts, understanding these underlying challenges is crucial for designing for manufacturability (DFM) and for managing project expectations. The difficulty comes down to three main material properties that work in combination.

The Big Three Challenges

To really see the difference, let’s compare a common stainless steel grade (304) with a very machinable material, 6061 aluminum.

| Property | 304 Stainless Steel | 6061 Aluminum | Impact on Machining |

|---|---|---|---|

| Work Hardening | High | Very Low | Material gets harder during cutting, increasing tool wear. |

| Thermal Conductivity | Low (16.2 W/m·K) | High (167 W/m·K) | Heat stays in the tool and part, not carried away by chips. |

| Ductility/Toughness | High | Medium | Creates long, stringy chips that are hard to manage. |

1. High Work Hardening

This is probably the biggest enemy. Work hardening, or strain hardening, means the material becomes harder and stronger when it’s bent, pressed, or cut. When a cutting tool moves through stainless steel, the pressure hardens the material right in front of the tool’s path. The cutting edge then has to cut through this newly hardened material, which requires even more force and generates more heat. It’s like trying to punch through a wall that gets stronger with every hit. This is why a hesitant or slow feed rate is disastrous; it gives the material time to harden, and the tool starts rubbing instead of cutting, leading to catastrophic tool failure.

2. Low Thermal Conductivity

Heat is the ultimate tool killer in machining. With materials like aluminum or carbon steel, most of the heat generated during cutting is carried away with the chip. This keeps the cutting tool and the workpiece relatively cool. Stainless steel is a poor conductor of heat. It holds onto heat like a thermos. This means the intense heat from the cutting action gets concentrated right at the tool’s tip and on the surface of the part. This extreme temperature can soften the cutting tool, cause it to wear down incredibly fast, and even deform or warp the part you are trying to machine accurately. This is why flood coolant isn’t just a suggestion when machining stainless—it’s a requirement.

3. High Ductility and Toughness

You might think of "toughness" as a good thing, but for a machinist, it can be a nightmare. Stainless steel is very ductile, meaning it stretches and deforms before it breaks. Instead of forming small, brittle chips that break away cleanly, it produces long, stringy, and gummy chips. These tough, continuous chips can wrap around the tool holder and the part, a condition we call a "bird’s nest." This can scratch the part’s surface, break the delicate cutting tool, and even stop the machine. This "gummy" nature also leads to a built-up edge (BUE), where tiny bits of the stainless steel literally weld themselves to the tool tip, ruining its geometry and destroying the surface finish of the component.

Why is it so hard to drill stainless steel?

You need to drill a simple hole in a stainless steel plate, but your drill bits are breaking, squealing, or burning out. This immediately stops your progress and makes you question your tools and your technique. Drilling stainless steel is uniquely difficult because it concentrates all the material’s worst properties into one tiny spot.

Drilling stainless steel is exceptionally hard because the drill tip is constantly engaging with work-hardened material from the previous rotation. The low thermal conductivity traps immense heat at this small contact point, leading to drill bit failure. Poor chip evacuation from the deep hole further compounds the problem, causing the gummy chips to jam the flutes, which leads to breakage.

I remember my early days in the shop vividly. I was tasked with drilling a series of holes in a thick 316 stainless steel flange. I snapped three expensive cobalt drill bits on a single part. It was a frustrating and costly lesson in just how unforgiving this material can be when drilled. The process creates a perfect storm for your drill bit, where everything that can go wrong, does.

A Perfect Storm for Your Drill Bit

Drilling is not like milling across a surface where there’s room for heat and chips to escape. It’s a confined operation that amplifies all of stainless steel’s challenging characteristics.

1. The Point of No Return

The very tip of the drill bit is where the battle is won or lost. As the drill rotates, the cutting edges are trying to shear the material, but the point is also applying immense pressure. This pressure work-hardens the bottom of the hole. On the next rotation, the drill has to cut through this newly hardened layer. If your feed rate is too timid, the drill will just rub against this hardened surface instead of cutting it. This rubbing action generates incredible friction and heat, annealing the drill tip (turning it blue and soft) and making it useless in seconds. You must maintain a constant, aggressive feed to ensure the drill is always digging under the work-hardened layer.

2. The Chip Evacuation Problem

The long, stringy chips produced by stainless steel are a major problem inside a confined hole. The flutes of a drill bit are designed to pull chips up and out. But stainless steel chips don’t break; they form long, tough ribbons. These ribbons clog the flutes, preventing chips from escaping and blocking coolant from reaching the cutting tip where it’s needed most. Once the flutes are clogged, the drill bit effectively gets stuck. The torque from the machine’s spindle has nowhere to go, and the result is almost always a snapped drill bit inside your expensive part.

3. The Right Tools and Techniques Are Not Optional

You simply cannot use the same tools and methods for stainless steel as you would for mild steel. Success requires a specific, deliberate approach.

| Feature | Recommended Approach for Stainless Steel Drilling | Why it Works |

|---|---|---|

| Drill Material | Cobalt (HSS-Co) or Solid Carbide | Resists the high temperatures and abrasion from chromium carbides. |

| Drill Point Angle | 135-degree split point | An aggressive angle helps penetrate hardened material and is self-centering. |

| Speed (RPM) | Lower than for mild steel (e.g., 40-70 SFM) | Reduces friction and heat generation at the cutting tip. |

| Feed Rate | Higher / Constant and Firm | Pushes the cutting edge beneath the work-hardened layer, preventing rubbing. |

| Coolant | High-pressure, high-volume flood coolant | Aggressively flushes chips out of the hole and cools the tool and workpiece. |

| Drilling Cycle | Peck Drilling (G83 cycle) | Retracts the drill periodically to break the long chips and clear the flutes. |

Using a technique called "peck drilling" is essential. The machine drills a small depth, then fully retracts the drill from the hole. This action breaks the long, stringy chip and allows coolant to flood the hole before the next "peck." It takes longer, but it’s the only reliable way to prevent chip jamming and tool breakage.

Why is stainless steel so hard to work with?

Beyond just the physics of cutting, managing a stainless steel project feels more complex and carries more risk. The material costs more, the machining takes much longer, and the chance of scrapping a valuable part is significantly higher. Acknowledging these factors and planning for them is how you successfully work with stainless steel.

Working with stainless steel is hard because it demands a complete system approach. It requires more rigid and powerful machines, specialized and expensive tooling, and carefully controlled cutting parameters. The higher material cost and slower machining speeds directly impact project budgets and timelines, demanding more careful planning and a higher level of expertise from the machinist.

When an engineer sends me a request for a quote, the choice of material is one of the biggest cost drivers. A part made from 316 stainless steel can easily be 3 to 5 times more expensive than the exact same part made from 6061 aluminum. This isn’t just about the raw material price. The difficulty of working with it affects every stage of the production process, from planning to final inspection. It’s a challenge that goes far beyond the cutting edge.

It’s More Than Just the Cut

To deliver a perfect stainless steel part on time and on budget, we have to consider the entire ecosystem of the job. It’s a test of our machines, our tools, and our people.

1. The Total Cost Factor

The final price of a machined part is a sum of multiple costs, and stainless steel inflates every single one of them.

- Material Cost: The raw bar stock for stainless steel is significantly more expensive than for carbon steels or aluminum. This is due to the costly alloying elements like nickel and chromium that give it its desirable corrosion resistance.

- Tooling Cost & Consumption: As I mentioned in my insights, tool wear is a huge factor. We must use premium carbide inserts with advanced coatings (like TiAlN or AlTiN) that can withstand the heat. Even then, these tools wear out much faster. This frequent tool replacement is a direct production cost that must be factored into the quote. A single job can consume multiple sets of inserts, whereas the same job in aluminum might use only one.

- Machine Time Cost: This is a hidden cost that many people overlook. You have to run the machines slower. Slower spindle speeds and feed rates are necessary to manage heat and tool pressure. If a part takes 10 minutes to machine in aluminum, it might take 30 or even 40 minutes in stainless steel. Since our machine time has a fixed hourly cost, longer cycle times mean a more expensive part.

2. The Expertise Factor

You cannot put an inexperienced machinist on a critical stainless steel job and expect good results. Machining this material is as much an art as it is a science. An experienced machinist develops a "feel" for it. They listen for the tell-tale squeal of a tool that’s about to fail. They watch the color and shape of the chips to know if the cut is stable. They know how to adjust the speeds and feeds on the fly to respond to how the material is behaving. This kind of hands-on expertise is invaluable and is a core part of what we provide at QuickCNCs. It’s the human element that prevents scrapped parts and ensures quality.

3. The Right Setup and Rigidity

The high cutting forces required for stainless steel will exploit any weakness in the machining setup. Rigidity is everything.

- Machine Tool: The CNC machine itself must be heavy, powerful, and rigid to absorb vibrations. Lighter-duty machines will chatter, leaving a poor surface finish and destroying tools.

- Workholding: The part must be clamped with extreme force and security. Any slight movement during the cut will lead to inconsistencies and potential tool breakage.

- Toolholding: Even the holder for the cutting tool must be high-quality and rigid to prevent any deflection under load. A solid setup is the foundation for any successful stainless steel machining project.

Conclusion

Machining stainless steel is tough because of its inherent properties of work hardening, poor heat transfer, and high ductility. Success demands the right tools, rigid machine setups, and deep expertise. By understanding these factors, you can better plan your projects and partner with experienced suppliers to achieve great results.