Struggling with complex grooves that cause tool breakage, poor surface finish, or long cycle times? These problems lead to scrapped parts and project delays, frustrating both engineers and managers. Mastering a few key programming strategies can solve these complex grooving challenges for good.

The best strategy combines the right tool, an optimal toolpath, and proper speed and feed settings. For complex grooves, avoid simple plunging. Instead, use multi-pass techniques like peck grooving or peel milling (ramping). This approach improves chip control, reduces tool pressure, and ensures higher accuracy and better surface finish on your parts.

Successfully machining a complex groove is about more than just a single G-code command. I’ve seen many projects get stalled because of a poor grooving strategy. It’s a process where every detail matters, from the tool you select to the path it takes. A small oversight can lead to big problems down the line. To get consistent, high-quality results, we need to look at the entire process step-by-step. Let’s break down what it takes to master these operations, starting with the tool itself.

How Do You Choose the Right Tooling for Complex Grooves?

Have you ever selected a grooving tool, only to have it chatter, break, or leave a terrible finish? The wrong tool wastes time and money, forcing you to rework setups and delaying production. This is a common frustration I see in many machine shops.

To choose the right tool, first match the insert geometry and grade to your material. For complex or deep grooves, select a rigid tool holder with the shortest possible overhang to minimize vibration. Also, consider modular systems with multiple head types for versatility in different grooving applications, like face or internal grooving.

Choosing the right tool is the foundation of any successful grooving operation. Over the years, I’ve learned that you can’t just grab any grooving tool off the shelf and expect perfect results, especially with complex profiles. You need to think about several factors together to prevent problems before they even start. A solid strategy here saves you from a lot of headaches later.

Key Factors for Tool Selection

The first thing my team and I look at is the tool’s rigidity. Vibration, or chatter, is the number one enemy in grooving. Most of it comes from the tool setup. We always follow a simple rule: keep the tool as short and stout as possible. The longer the tool overhangs from the holder, the more it will want to vibrate. We also select tool holders with the largest possible cross-section that the machine turret and workpiece will allow. This creates a more stable cutting foundation. For deep grooves, a carbide-reinforced or heavy metal boring bar can make a huge difference in damping vibrations.

Insert Geometry and Grade

Next, we focus on the insert itself. This is where the real "cutting" decision is made. The geometry of the insert needs to match the groove you are cutting. But it’s also about chip control. For a material like aluminum that produces long, stringy chips, we’d choose an insert with a sharp edge and a high-rake chipbreaker. For harder materials like stainless steel, we’d use a stronger insert with a tougher edge and a coating like TiAlN to handle the heat.

Here’s a quick table to show how we think about it:

| Material Type | Recommended Insert Geometry | Recommended Grade/Coating | Why? |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aluminum | Sharp, positive rake | Uncoated or PVD (e.g., TiB2) | Prevents built-up edge and clears chips easily. |

| Low-Carbon Steel | Moderate rake, effective chipbreaker | PVD or CVD coated (e.g., TiN) | Good balance of toughness and chip control. |

| Stainless Steel | Tough cutting edge, honed | PVD coated (e.g., TiAlN) | Resists heat, chemical wear, and notching. |

| Cast Iron | Strong negative rake edge | CVD coated or CBN | Excellent wear resistance for abrasive material. |

By carefully matching the tool holder, insert geometry, and material grade, we set ourselves up for a much smoother and more reliable machining process.

What Are the Most Effective Toolpath Strategies for Grooving?

Do you find your machine stuck in a cycle of slow, cautious plunging for every groove? This method is not only inefficient but also puts immense stress on your tools and parts. It often leads to poor chip evacuation and broken inserts, killing your productivity.

The most effective toolpath strategies move beyond simple plunging. Use multi-pass turning for wide grooves, peck grooving for deep grooves, and ramping or peel grooving for high-efficiency machining. These methods break the cut into smaller, manageable steps, which drastically reduces tool pressure, controls chips, and improves overall surface finish.

Back when I was starting out on the shop floor, the standard approach was to just plunge the tool straight in, retract, and repeat. This works for simple, shallow grooves. But for anything complex, this method is a recipe for disaster. I learned the hard way that a smart toolpath is your best friend. It can turn a difficult job into a routine one. Different grooves require different approaches, and knowing which strategy to use is what separates an average machinist from a great one.

Moving Beyond the Plunge

The simple plunge cut is fast to program but creates high cutting forces. The tool is engaged on three sides, which traps heat and makes it very difficult for chips to escape. This is why we almost always avoid it for grooves that are deeper than they are wide.

Multi-Pass and Peck Grooving

Our go-to method for most grooves is a multi-pass strategy. Instead of one big cut, we take several smaller ones. For a wide groove, we might plunge on one side, then make a series of side-turning cuts to open it up to the full width. This changes the cutting dynamics so the tool is primarily cutting on one side, which is much more stable.

For deep, narrow grooves, we use peck grooving. Think of it like a woodpecker. The tool plunges to a shallow depth, retracts fully to clear chips, plunges a little deeper, and repeats. This cycle prevents chips from getting packed into the groove, which is a major cause of tool failure. Most modern CNC controls have a G75 cycle for this, but you can also program it manually.

Advanced Ramping and Peel Grooving

For the highest efficiency, especially in stronger materials, we use ramping or peel grooving. Instead of plunging straight down, the tool moves down and sideways at the same time, essentially following a diagonal or helical path. This method keeps the engagement angle low and creates thin, manageable chips. It allows for much higher feed rates and significantly reduces cycle times. This is my favorite technique because it feels like you are "peeling" the material away smoothly instead of forcing the tool through it. It requires good CAM software but the results are incredible.

How Can You Overcome Common Challenges Like Chip Control and Vibration?

Are you constantly stopping your machine to clear out tangled chips or hearing that awful squeal of chatter during a cut? These two problems, poor chip control and vibration, can ruin a part in seconds. They create production bottlenecks and make it impossible to run a reliable, lights-out operation.

To control chips, use inserts with aggressive chipbreakers and apply high-pressure coolant directly at the cutting edge. To combat vibration, use the shortest, most rigid tool holder possible and adjust your cutting speed. Sometimes, slightly reducing the RPM can move you out of a harmonic frequency and stop the chatter instantly.

I remember one particularly difficult project involving deep grooves in 316 stainless steel. We were fighting birds’ nests of chips and terrible chatter on every single part. The job was falling behind schedule. We solved it by methodically addressing both issues. It wasn’t one magic fix, but a combination of small adjustments that made all the difference. Chip control and vibration are linked. If you solve one, you often help solve the other.

A Systematic Approach to Chip Control

Good chip control starts with your programming. You want to create chips that are short, curled, and break off cleanly. Long, stringy chips will wrap around the tool and workpiece, leading to a bad finish or even tool breakage.

Here’s how we tackle it:

- Insert Choice: We always start with an insert that has a chipbreaker designed for the material and depth of cut. A "-GF" (Grooving, Finishing) geometry is great for light cuts, while a "-GM" (Grooving, Medium) works for more general-purpose use.

- Cutting Parameters: We aren’t afraid to increase the feed rate. Sometimes, a feed rate that is too low will "rub" the material instead of cutting it, creating a stringy chip. A slightly higher feed rate can force the chip to form and break properly.

- High-Pressure Coolant: This is a game-changer. A strong jet of coolant aimed directly into the groove does two things. It cools the cut, which is critical. But more importantly, it physically blasts the chips out of the way before they can cause a problem. We try to use at least 1,000 PSI (70 bar) for tough grooving jobs.

Taming Vibration (Chatter)

Vibration is a resonance issue that happens when the cutting frequency matches the natural harmonic frequency of the tool, holder, or workpiece.

Here’s our checklist for fighting chatter:

- Tool Setup: As I mentioned before, rigidity is king. Shortest possible overhang, largest possible tool shank. Double-check that all screws are torqued correctly.

- Cutting Speed: This is the easiest parameter to adjust on the fly. Chatter occurs within specific RPM ranges. If you hear chatter, try reducing the spindle speed by 10-15%. Often, this is enough to move out of the harmonic zone and quiet the cut. If that doesn’t work, try increasing it.

- Toolpath Strategy: A ramping or peel grooving toolpath naturally reduces vibration because the cutting forces are lower and more consistent than in a plunge cut. Changing your toolpath from a 90-degree plunge to a 45-degree ramp can make a world of difference.

By systematically working through these points, my team and I can stabilize even the most challenging grooving operations.

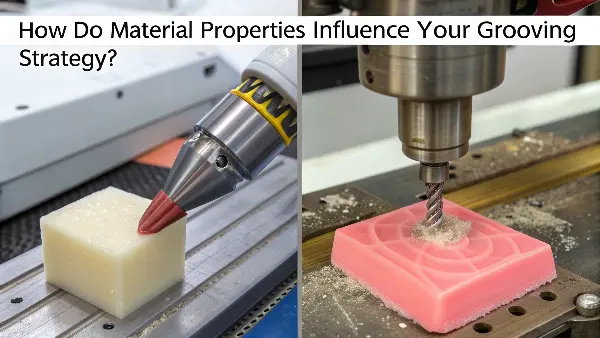

How Do Material Properties Influence Your Grooving Strategy?

Do you assume the same grooving program will work for aluminum and then for Inconel? Using a one-size-fits-all approach is a fast way to break tools, scrap expensive material, and miss deadlines. Every material behaves differently, and your strategy must adapt to its unique properties.

Your strategy must change based on the material’s hardness, ductility, and thermal conductivity. For soft, gummy materials like aluminum, focus on high speeds and sharp tools to avoid built-up edge. For hard, heat-resistant superalloys like Inconel, use lower speeds, tough-edged tools, and a peel grooving strategy to manage extreme heat and pressure.

In my experience, material is the single biggest variable. One of my first big lessons as an engineer was watching a senior machinist switch from machining steel to titanium. He changed almost everything: the tool, the speeds, the feeds, the coolant, and the toolpath. He explained that you don’t fight the material; you work with it. Understanding how a material wants to be cut is crucial for success, especially in a demanding operation like grooving. It dictates every other choice you make.

Strategy for Soft Materials

Let’s start with easier materials like aluminum and brass. These materials have low hardness and high thermal conductivity, meaning heat dissipates quickly. The biggest challenge here is not heat or tool wear, but built-up edge (BUE) and chip control. Soft material can weld itself to the cutting edge, ruining the surface finish.

- Tooling: Use uncoated, very sharp inserts, often with a polished surface (PVD TiB2 coatings are also excellent).

- Speeds and Feeds: Run at high surface speeds to stay ahead of BUE formation. Use a moderate to high feed rate to ensure a chip is formed instead of the material being smeared.

- Coolant: A flood of water-soluble oil is usually sufficient to wash chips away and prevent BUE.

Strategy for Hard Materials and Superalloys

Now let’s look at the other end of the spectrum: stainless steels, titanium, and Inconel. These materials are tough, work-harden easily, and are poor thermal conductors. All the heat from the cut gets concentrated on the tool’s cutting edge.

- Tooling: Use inserts with a very tough, often honed (rounded) cutting edge to prevent chipping. Advanced PVD coatings like TiAlN or AlCrN are essential to act as a thermal barrier.

- Speeds and Feeds: Run at much lower surface speeds to manage heat. A consistent, moderate feed rate is critical. If you stop the tool in the cut, the material will work-harden instantly, making it much harder to re-engage.

- Toolpath: This is where peel grooving or ramping strategies are not just better—they are essential. These toolpaths keep tool engagement low and predictable, which helps manage cutting forces and prevents catastrophic heat buildup. You should never plunge-cut a deep groove in a superalloy.

Here’s a comparison table summarizing the strategic shifts:

| Factor | Aluminum (Soft) | Inconel (Hard) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Challenge | Built-Up Edge (BUE) | Extreme Heat & Work Hardening |

| Cutting Speed | High (e.g., 300-600 m/min) | Low (e.g., 20-40 m/min) |

| Feed Rate | Moderate to High | Low to Moderate, but constant |

| Tool Edge | Very Sharp | Tough, Slightly Honed |

| Tool Coating | Uncoated or TiB2 | TiAlN, AlCrN |

| Toolpath | Multi-pass turning is fine | Peel grooving/Ramping is best |

| Coolant | Flood Coolant | High-Pressure Coolant (Essential) |

Adapting your approach based on these material properties will dramatically increase your success rate with complex grooves.

Conclusion

In summary, mastering complex grooving requires a holistic strategy. It involves selecting the right tools, using smart toolpaths, controlling chips and vibration, and adapting your approach for each material.