You have perfected your design, every surface and feature is exactly where it needs to be. But when the manufacturing quote arrives, it’s shockingly high. You are left wondering what could have possibly driven the cost so far beyond your budget, making you rethink the entire project.

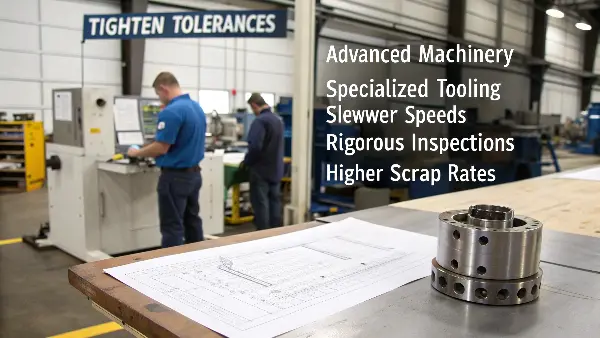

Yes, tightening a tolerance almost always increases manufacturing costs. The increase isn’t small. It happens because achieving higher precision demands more advanced machinery, specialized and more expensive tooling, slower machining speeds, and much more rigorous quality inspection processes. A higher scrap rate is also a major factor, as parts that fall just outside the narrow acceptable range must be discarded, and this risk is priced into your quote.

Understanding the "why" behind this cost increase is the first step toward becoming a more effective engineer or designer. It is not just about making a part; it is about making a part that functions perfectly without unnecessary expense. I have seen countless projects where a simple review of tolerances saved thousands of dollars without affecting the final product’s performance. In this article, I will break down exactly how and where those costs add up so you can make smarter, more cost-effective design decisions.

Will tightening a tolerance increase the cost of manufacturing?

You are trying to keep your project on budget, but you also need parts that fit together perfectly. You look at your drawing and specify a very tight tolerance, thinking it is the safest option. But this decision might be the very thing that inflates your manufacturing costs significantly.

Absolutely. Tightening a tolerance directly increases manufacturing costs, often exponentially. Moving from a standard tolerance (e.g., ±0.1 mm) to a tight one (e.g., ±0.01 mm) requires a machinist to use more precise machines, take multiple lighter cuts, slow down the process, and use special tools. All of this adds significant time and labor, which are the primary drivers of cost in CNC machining.

The Exponential Cost Curve

The first thing to understand is that the relationship between tolerance and cost is not linear. It is exponential. This means that making a tolerance twice as tight can make the part four, or even eight, times more expensive. For example, machining a part to within ±0.1mm might be a standard operation. But changing that to ±0.01mm is a completely different challenge. It is the difference between measuring with a standard ruler and measuring with a high-powered microscope.

I remember a project with a client from Germany, an engineer much like Alex. He designed a simple aluminum shaft. His initial drawing called for a diameter tolerance of ±0.005mm along its entire length. The quote was high, and he asked why. I explained that holding such a tolerance required a cylindrical grinding operation after turning, a completely separate process with a different machine and operator. We reviewed the design together. It turned out only one small section of the shaft needed that precision for a bearing fit. By relaxing the tolerance on the rest of the shaft to a standard ±0.05mm, we cut the part’s cost by nearly 60%. The part functioned identically in the final assembly. This shows how a small change can have a massive financial impact.

Why Standard Tolerances Are More Affordable

Machining shops like ours build their processes around efficiency. Standard tolerances (often around ±0.1mm or ISO 2768-m) are considered "standard" because they can be achieved reliably and quickly with general-purpose CNC machines and tools. The machinist can run the machine at optimal speeds and feeds, producing parts quickly with a very low scrap rate. The inspection can be done with standard tools like digital calipers. When you specify a tolerance tighter than this, you push the process out of that efficient window.

Here is a simplified look at how cost might change for a basic part:

| Tolerance Level | Relative Cost | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| ±0.25 mm (Loose) | 1x | Very easy to machine, fast cycle time. |

| ±0.1 mm (Standard) | 1.5x | Achievable with standard CNC practices. |

| ±0.05 mm (Fine) | 3x | Requires more careful setup, slower speeds. |

| ±0.01 mm (Precision) | 8x | May need grinding, special inspection (CMM). |

| < ±0.005mm (High-Precision) | 15x+ | Requires specialized machines, environment control. |

Always ask yourself: "Does this feature really need this level of precision?" If it’s not for a critical fit, like a bearing seat or a press-fit pinhole, you can probably save a lot of money by using a standard tolerance.

How do tolerances impact the manufacturing process?

You have sent your CAD file to the machine shop, but the machinist calls back with questions. They ask if the tight tolerance on a non-critical surface is really necessary. You wonder why it matters so much to them, as they are just programming a machine to cut the part you designed.

Tolerances fundamentally change the entire manufacturing workflow. Tighter tolerances dictate the choice of machine, the cutting tools used, the number of operations, the machining time, and the inspection method. A tight tolerance forces a machinist to slow down, take extra steps, and use more expensive equipment to ensure the part is made correctly, which directly impacts lead time and cost.

Machine Selection and Setup Time

Not all CNC machines are created equal. A standard 3-axis mill might be perfect for parts with tolerances of ±0.1mm. But if you need ±0.01mm, we have to use a high-precision 5-axis machine that is kept in a temperature-controlled room. These machines are more expensive to buy and maintain, so the hourly rate is higher.

The setup process also becomes much more complex. For a standard part, an operator might set it up in 30 minutes. For a high-precision part, the setup could take hours. The machinist must indicate the part to ensure it is perfectly aligned, check for any runout in the tooling, and run test cuts. Every step must be deliberate and double-checked because the margin for error is almost zero. A tiny vibration or a slight change in temperature can throw the part out of tolerance. I once worked on a set of components for a medical device where a single fingerprint left on the part before a final pass was enough to affect the surface measurement. That is the level of care required.

Cutting Speeds, Tooling, and Extra Operations

To hold a tight tolerance, a machinist cannot just cut the material away in one go. They must use a strategy of roughing and finishing passes. The roughing pass removes most of the material quickly, leaving a small amount behind. The finishing pass is a very slow, light cut that removes the last bit of material to produce the final dimension and surface finish. This slow pass minimizes tool pressure, heat, and vibration, all of which can affect accuracy. This multi-pass approach takes significantly more machine time.

The choice of cutting tools is also critical. For standard work, we might use general-purpose carbide end mills. For precision work, we might use brand-new, high-performance tools for every new part to ensure there is no wear. Sometimes, machining alone is not enough. To achieve very tight tolerances on holes, we might need to add secondary operations like reaming or honing. For flat surfaces, we might need to use a surface grinder after milling. Each of these extra steps adds more time, labor, and cost to the process. It requires moving the part to a different machine, setting it up again, and performing another operation.

How can a smaller tolerance affect the cost of a product?

You receive a quote for a prototype, and the price per part seems high. You know tighter tolerances increase costs, but you want to understand exactly where that money is going. Is it the material? Is it the labor? Knowing this helps you justify the budget or find ways to reduce the cost.

A smaller tolerance affects the direct and indirect costs of a product. Direct costs rise due to increased labor for skilled machinists and longer machine run times. Indirect costs also climb because of the need for specialized, expensive inspection equipment, a higher potential for material waste through scrapped parts, and the higher overhead associated with maintaining precision machinery and environments.

Direct Costs: Labor and Machine Time

The most visible costs are labor and machine time. A part with a ±0.01mm tolerance cannot be handed to just any operator. It requires a senior machinist with years of experience, and their time is more valuable. They spend more time not just watching the machine, but actively planning the process, selecting the right tools, and making micro-adjustments.

Machine time is the other major direct cost. Let’s say a simple part takes 10 minutes to machine to a standard tolerance. To hold a tolerance ten times tighter, the machine might need to run at half the speed and take three times as many passes. The cycle time could easily jump to 30 or 40 minutes. Since machine shops charge by the hour, this directly triples or quadruples the cost. I saw this with a client who needed a series of gears for a planetary gearbox. The tolerance on the tooth profile was extremely tight. The parts spent hours on a 5-axis machine, moving very slowly, to get the profile just right. The machine time became the single largest cost factor in the final price of each gear.

Indirect Costs: Inspection, Scrap, and Tooling

The costs you do not see on the timesheet are just as important. Quality control is a huge one. For a standard tolerance, we can check a part in 30 seconds with a pair of calipers. For a tight tolerance part, that is not good enough. We have to take it to our quality lab and use a Coordinate Measuring Machine (CMM). A CMM program can take an hour to write and 15-20 minutes to run for each part. That is expensive inspection time.

The scrap rate is another hidden cost. When the acceptable range is wide, almost every part is good. When the tolerance is very tight, a small error means the entire part must be thrown away. A good shop factors this risk into the quote. If they predict a 10% scrap rate, they will build the cost of making 110 parts into the price for 100. Finally, tooling costs go up. High-precision machining causes tools to wear faster, and we often use more expensive, specialized tools (like diamond-tipped cutters or custom-ground end mills) that can add hundreds of dollars to the job cost. These indirect costs can easily add 30-50% to the total price.

What impact do tolerances have on the production, assembly, and cost of a product?

You are designing a complex assembly with dozens of interlocking parts, like a robotic arm. You know that if the parts do not fit together perfectly, the entire product will fail. So you specify tight tolerances on everything, assuming it is the only way to guarantee a successful assembly and a high-quality product.

Tolerances have a cascading impact. In production, tight tolerances slow down cycle times and increase scrap, raising costs. In assembly, they can be a major benefit, allowing parts to fit together smoothly and reliably, reducing assembly time. The key is in finding a balance. Over-tolerancing parts unnecessarily inflates the total product cost, while under-tolerancing can lead to costly assembly failures.

Production: The Ripple Effect

In the production phase, tight tolerances create a ripple effect that goes beyond a single part. Because each part takes longer to machine, the overall production schedule gets longer. If you need 1,000 units, and each one takes an extra 20 minutes to machine due to tight tolerances, that adds over 330 hours of machine time to the project. This can delay your product launch and tie up capital. It also puts more strain on the machine shop’s capacity.

This is why communication with your manufacturer is so important. I often work with engineers like Alex to perform a Design for Manufacturing (DFM) review. We look at every single tolerance on a drawing. I’ll ask, "Is this tolerance for a fit, a function, or just a clearance hole?" Many times, an engineer has simply used a default tight tolerance across the entire part. By identifying which three or four features are truly critical, and relaxing the tolerances on the other twenty features, we can dramatically reduce production time and cost without sacrificing any performance. It’s about being strategic, not just strict.

Assembly: The Hidden Benefit (or Cost)

This is where tight tolerances can actually save you money. If you are building a complex product, like a transmission or a scientific instrument, assembly can be a huge portion of the labor cost. When parts are made with precise tolerances, they slide together perfectly every time. Assembly is fast, predictable, and requires less skill. You avoid situations where a technician is sitting there with a file or a hammer, trying to force parts to fit. This reliability is a hidden benefit of paying more for precision machining.

However, there’s a flip side. If you have not done a proper tolerance stack-up analysis, you can run into big problems. Tolerance stack-up is what happens when the small variations in each part add up across an entire assembly. Even if every part is within its own tolerance, the combined variation can cause the final assembly to fail. For example, if you have ten plates stacked together, and each has a thickness tolerance of ±0.05mm, the total stack height could vary by as much as ±0.5mm. If that stack needs to fit into a housing with a gap of only ±0.2mm, it will not work. This is why it is critical to analyze the whole system, not just individual parts.

Conclusion

In summary, tightening manufacturing tolerances directly increases costs due to the need for advanced machines, skilled labor, and rigorous inspection, making strategic tolerance selection essential for cost-effective design.