Are you struggling to get your machined parts back with the exact strength and durability you designed for? Miscommunication about heat treatment can lead to parts failing under stress, causing costly rework and project delays. Clearly defining these requirements on your drawings is the key to getting it right the first time.

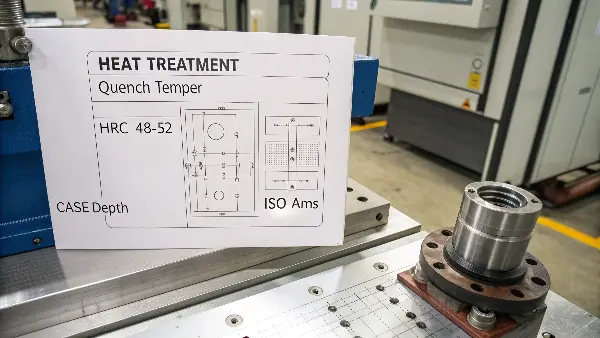

To specify heat treatment, you must clearly note four key things on your drawing: the heat treatment process (e.g., quench and temper), the required hardness range (e.g., HRC 48-52), the case depth for surface treatments, and a reference to any industry standard (like ISO or AMS). This information should be placed in the general notes section or near the title block to avoid any confusion for the manufacturer.

Getting the callout right is the first and most critical step. I’ve seen countless projects go sideways because of a vague note like "harden part." The manufacturer is left guessing, which is a recipe for disaster. But when you provide clear, specific instructions, you remove all doubt and empower your manufacturing partner to deliver exactly what you need. Let’s break down how to do this effectively to ensure your parts are perfect every time.

How do you specify heat treatment on a drawing?

You’ve spent hours perfecting a component’s design, but how do you ensure the final part has the necessary mechanical properties? Simply writing "heat treat" on your drawing is a gamble. Vague instructions open the door to misinterpretation, leading to parts that are too soft, too brittle, or completely unusable for their intended purpose. A clear, standardized callout on your drawing is the only way to guarantee success.

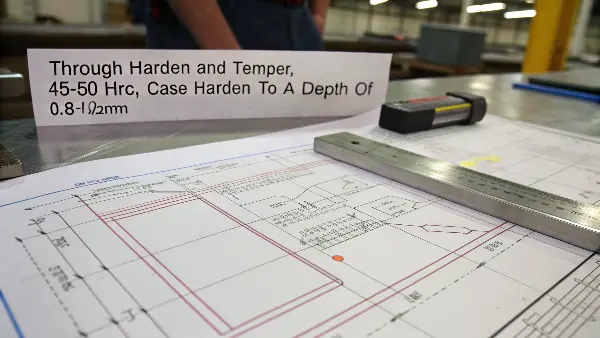

To properly specify heat treatment, your drawing note should include the process name (e.g., "Through Harden and Temper"), the final required hardness and its scale (e.g., "45-50 HRC"), and the case depth for surface treatments (e.g., "Case Harden to a depth of 0.8-1.2mm"). This note must be located in a prominent place, either in the general notes section or directly beside the title block’s material specification.

In my experience, clarity here saves more time and money than almost any other part of the design process. A well-defined note acts as a legal contract between you and the machine shop. It leaves no room for error. Let’s look at the essential elements your note must contain to be effective.

Key Elements of a Heat Treatment Callout

Your note should be concise but comprehensive. Think of it as giving the machinist a complete recipe. Anything less invites questions and potential mistakes. Here are the core components you need to include:

-

Process Name: Always state the exact process required. Don’t just say "harden." Be specific. Examples include "Anneal," "Normalize," "Quench and Temper," "Carburize," or "Nitride." Each process yields different results, so this is your first and most important instruction.

-

Hardness Requirement: This is non-negotiable. You must specify the target hardness value and the scale. The most common scales are Rockwell (HRC for hard steels, HRB for softer metals), Brinell (HB), and Vickers (HV). Always provide a range, not a single number. For example, "Harden to 48-52 HRC" gives the operator a realistic target to hit. A single value is often impossible to achieve perfectly and can lead to higher scrap rates.

-

Case Depth (for surface treatments): For processes like carburizing, nitriding, or induction hardening, the hardness is only on the surface. You must specify how deep this hardened layer, or "case," should be. For example: "Carburize and Harden to a case depth of 0.7-1.0 mm. Surface hardness to be 58-62 HRC." You might also specify the effective case depth, which is the depth to a specific hardness value.

-

Areas to be Treated: Sometimes, only specific features of a part need to be hardened, like gear teeth or bearing surfaces. Use a phantom line or cross-hatching on your drawing to clearly indicate these areas. Accompany this with a note like "Harden indicated surfaces only." This prevents the entire part from becoming brittle and can save on costs.

By breaking down your requirements into these four key areas, you create a callout that is impossible to misunderstand. This simple practice has saved my clients from countless headaches and ensured their parts perform as expected right out of the box.

How do you select the right heat treatment process?

Choosing the right material is only half the battle. Now you need to select a heat treatment process that unlocks that material’s full potential. With so many options available, it’s easy to feel overwhelmed. Picking the wrong one can mean your part fails prematurely, even if it’s machined perfectly. The key is to match the process to your part’s application and material type to achieve the desired outcome.

To select a heat treatment process, first define your primary goal: do you need uniform hardness throughout (through hardening), a hard surface with a tough core (case hardening), or to soften the material for machinability (annealing)? Then, match this goal with your material type. For example, high-carbon steels are great for through hardening, while low-carbon steels require case hardening processes like carburizing.

Over the years, I’ve helped hundreds of engineers navigate this choice. The most common mistake I see is focusing only on hardness a specific process without considering the material or the part’s geometry. The process and material work together. Let’s compare the main categories to help you decide.

Comparing Heat Treatment Families

Think of heat treatment processes in terms of their main purpose. Do you want to make the entire part hard, just the surface, or make it softer? This initial question will narrow down your options significantly.

| Process Category | Primary Goal | Common Processes | Best For… |

|---|---|---|---|

| Through Hardening | Achieve uniform hardness and strength through the part. | Quenching and Tempering | Medium/high-carbon steels (e.g., 4140, 1045), tool steels (A2, D2). |

| Case Hardening | Create a hard, wear-resistant surface with a ductile core. | Carburizing, Nitriding, Induction | Low-carbon steels (e.g., 1018, 8620), gears, shafts, components under high surface wear. |

| Annealing/Softening | Soften the material, relieve stress, improve machinability. | Annealing, Normalizing, Stress Relieving | Any metal that has been cold-worked or needs to be machined extensively before final hardening. |

Through Hardening is ideal for components that face high tensile and torsional loads, like structural bolts or axles. The goal is to make the entire cross-section of the part strong. You achieve this by heating the steel to a high temperature, rapidly cooling it (quenching), and then reheating it to a lower temperature (tempering) to reduce brittleness and achieve the target hardness.

Case Hardening, on the other hand, is for parts that need a very hard surface to resist wear but a softer, tougher core to absorb shock without cracking. Think of gears. The teeth need to be incredibly hard, but the main body of the gear needs to be able to handle impact. Processes like carburizing add carbon to the surface of a low-carbon steel, allowing just the outer layer to be hardened.

Annealing and related processes are essentially a "reset" button for metal. They are used to make a material softer and easier to machine, or to remove internal stresses built up during manufacturing. You almost always perform these treatments before final machining and hardening.

The best choice always comes back to your application. What problem are you trying to solve? Wear resistance, core strength, or impact toughness? Answering that question will point you directly to the right process family.

Should you heat treat before or after machining?

One of the most critical decisions you’ll make is the timing of your heat treatment. Do you machine the part to its final dimensions and then harden it, or do you harden the raw material first and then machine it? This choice has major consequences for cost, dimensional accuracy, and the feasibility of your entire project. There’s no single right answer, and getting it wrong can be very expensive.

For a majority of parts, you should perform rough machining first, then heat treat, and finally finish machining. This "rough-heat treat-finish" sequence balances machinability with accuracy. It removes the bulk of the material when it’s soft, then accounts for any distortion from heat treatment during the final machining stage, ensuring tight tolerances are met.

I remember a client who insisted on fully machining a complex part from 4140 steel and then sending it for through-hardening. The part warped so much during quenching that it was completely out of spec. They had to scrap the entire batch. This is a classic example of why understanding the sequence is so important. Let’s break down the pros and cons of each approach.

Analyzing the Machining Sequence

The decision to heat treat before or after machining is a trade-off between ease of manufacturing and final part quality. Your choice depends heavily on the material, the complexity of the part, and the required tolerances.

Path 1: Machine, then Heat Treat

This approach involves machining the part to its final or near-final dimensions from an annealed (soft) material, and then applying the heat treatment.

-

Pros:

- Easier & Faster Machining: Working with soft material is much faster. It reduces tool wear and machining time, which lowers the cost.

- Good for Complex Geometries: Intricate features are easier to create in a soft state.

-

Cons:

- Distortion Risk: Heat treatment, especially quenching, introduces stress that can cause the part to warp, twist, or change dimensions. For tight-tolerance parts, this is a major problem.

- Surface Finish Issues: The heating and quenching process can create a layer of scale or discoloration on the surface, which may require secondary cleaning or grinding operations.

- Risk of Cracking: Thin sections or sharp internal corners can become stress points and may crack during quenching.

Path 2: Heat Treat, then Machine (Hard Machining)

This involves hardening the raw material blank first and then performing all machining operations on the hardened material. This is often called "hard machining."

-

Pros:

- Excellent Dimensional Stability: Since the heat treatment is done first, there is no risk of the final part distorting. This is the best method for achieving very tight tolerances.

- Superior Surface Finish: Machining after hardening can produce excellent surface finishes without the need for post-treatment grinding.

-

Cons:

- Difficult & Expensive Machining: Cutting hardened steel is slow and requires special, expensive tools (like CBN or ceramic inserts). Tool life is short, and machine time is long, driving up the cost significantly.

- Design Limitations: It’s very difficult to machine complex features, small holes, or sharp internal corners in hardened material.

The Best of Both Worlds: The "Rough-Heat Treat-Finish" Strategy

For high-precision parts, the most reliable and common approach is a hybrid:

- Rough Machine: Machine the part from soft material, leaving a small amount of extra stock (e.g., 0.2-0.5 mm) on critical surfaces.

- Heat Treat: Harden the semi-finished part.

- Finish Machine/Grind: Use hard machining or grinding to remove the final layer of stock, bringing the part to its exact dimensions and correcting for any distortion that occurred during heat treatment.

This method gives you the best balance of cost, speed, and precision. It’s the industry standard for a reason.

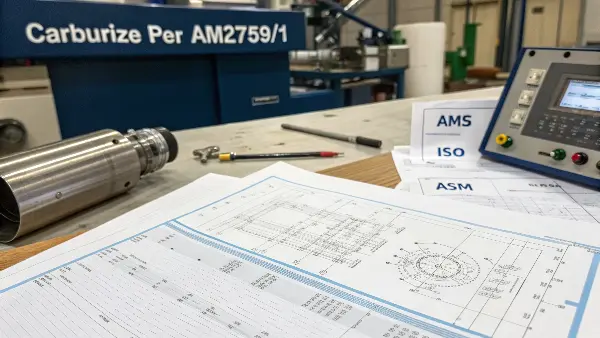

What industry standards should you reference for heat treatment?

You’ve selected the right process and defined your hardness, but how do you ensure global suppliers understand your requirements in the same way? Referencing an industry standard is the answer. Standards are a universal language for manufacturing. Using them on your drawings removes ambiguity and ensures consistency, no matter where your parts are made. Neglecting them opens the door to regional interpretations and inconsistent quality.

You should reference established industry standards like AMS (Aerospace Material Specifications), ISO (International Organization for Standardization), or ASTM (American Society for Testing and Materials) in your heat treatment callouts. For example, instead of just saying "Carburize," you can specify "Carburize per AMS2759/1." This directs the manufacturer to a specific document outlining the exact process controls, testing, and quality requirements.

When I work with clients like Alex in Germany, referencing an ISO standard is critical. It ensures that my team in China and his quality team in Europe are evaluating the part against the exact same criteria. It creates a shared foundation of trust and quality assurance. Without it, you’re relying on a supplier’s internal, and often undocumented, practices.

Key Standards for CNC Machining Heat Treatment

Different industries and regions have their preferred standards, but many are globally recognized. Including one on your drawing elevates your technical documentation from a simple request to a professional, enforceable specification.

Here are some of the most common standards you should know:

| Standard Body | Common Application | Example Specification | What It Governs |

|---|---|---|---|

| AMS | Aerospace and high-performance applications. Very detailed and strict. | AMS2759: Heat Treatment of Steel Parts, General Requirements AMS-H-6875: Heat Treatment of Steel Raw Materials |

Furnace temperature uniformity, atmosphere control, process parameters, inspection procedures, and documentation. |

| ASTM | General engineering, materials testing, and broad industrial use in North America. | ASTM A941: Terminology Relating to Steel, Stainless Steel, Related Alloys, and Ferroalloys | Provides standardized definitions for heat treatment terms, ensuring everyone uses the same vocabulary. |

| ISO | International standard, widely accepted in Europe and globally. | ISO 17663: Welding — Quality requirements for heat treatment in connection with welding and allied processes | While focused on welding, its principles on quality systems for heat treatment are widely referenced for general manufacturing. |

| SAE | Automotive and ground vehicle industries. Often overlaps with AMS and ASTM. | SAE J415: Definition of Heat-Treating Terms | Similar to ASTM, it provides definitions. Many material specifications (like SAE 4140) have implied heat treatment guidelines. |

By adding a simple line like "Heat treat per AMS2759" to your callout, you are incorporating a massive amount of technical detail without cluttering your drawing. You are telling your supplier that you expect them to follow a documented, controlled, and verifiable process. This is especially important when outsourcing internationally. It protects you from suppliers who might cut corners on furnace calibration or process control to save money. For any engineer serious about quality, referencing the proper standard is a non-negotiable step.

Conclusion

In summary, clear heat treatment specifications are vital for part performance. By defining the process, hardness, and applicable standards on your drawings, you ensure your design intent is met consistently.