Are you tired of unexpected equipment downtime caused by broken shafts? A single failure can halt production, lead to costly repairs, and put immense pressure on your engineering team. Understanding the root cause is the first step toward building more reliable machines and avoiding future headaches.

The most common transmission shaft failures are fatigue fracture, wear, corrosion, and permanent deformation (bending). Fatigue fracture from repeated loading is the number one cause. Preventing these failures involves selecting the right material, optimizing the design to reduce stress, ensuring proper lubrication, and avoiding operational overloads and misalignment.

I’ve been in the manufacturing world for over a decade, first on the shop floor and now helping engineers worldwide source custom CNC parts. I’ve seen firsthand what happens when a critical shaft fails. It’s not just about a broken piece of metal; it’s about the entire system it supports. In this post, I want to walk you through the ways shafts and their related components fail. More importantly, I’ll share the practical strategies we use to help our clients design and manufacture shafts that last. Let’s dive in.

What are the main failure modes of a shaft?

You’ve specified a robust material and checked your calculations, but a shaft in the field just failed. It’s a frustrating situation that can make you second-guess your design. Let’s look at the four common culprits behind these failures so you can identify and prevent them effectively.

A shaft typically fails in one of four ways: fatigue fracture from cyclic stress, wear from friction between moving parts, corrosion from environmental exposure, and plastic deformation from a sudden overload. Fatigue is the most common, as microscopic cracks grow over time until the shaft suddenly snaps without warning.

Over the years, I’ve analyzed countless failed components with my clients. Understanding these failure modes is like being a detective. The evidence on the broken part tells you exactly what happened. Here’s a deeper look at what you should be looking for.

1. Fatigue Fracture

This is the silent killer of shafts. It doesn’t happen because of one massive overload. It happens because of millions of small, repetitive stress cycles. Think about a shaft turning a pump, constantly under a bending load. Even if the load is well within the material’s strength limits, tiny microscopic cracks can form at stress concentration points.

These points are usually design features like:

- Sharp corners where the diameter changes

- Keyways

- Drilled holes

- Even rough surface finishes or minor scratches

Once a crack starts, each rotation of the shaft causes it to open and close, slowly growing deeper. On the fracture surface, this often leaves behind tell-tale signs called "beach marks," which look like ripples in the sand. Eventually, the remaining cross-section of the shaft is too small to handle the load, and it fails suddenly and catastrophically. This is the most dangerous mode because there’s often no visible warning before the final break.

2. Wear

Wear happens when material is gradually removed from the shaft’s surface due to mechanical action. It leads to a loss of dimension, increased clearances, and reduced operational precision. There are a few types:

- Abrasive Wear: Caused by hard particles (like dirt, sand, or metal debris) getting into the lubricant and scratching the shaft surface like sandpaper.

- Adhesive Wear: Occurs when two surfaces slide against each other under high pressure, causing microscopic points to weld together and then tear apart. This is common in poorly lubricated conditions.

- Fretting Wear: This is a tricky one. It happens between two surfaces that are supposed to be tightly fitted together, like a bearing press-fit onto a shaft. Tiny vibrations cause microscopic rubbing, which creates oxide debris and can initiate fatigue cracks.

3. Corrosion

Corrosion is a chemical attack on the shaft’s surface. It’s usually caused by moisture, chemicals, or operating in a humid environment. Rust is the most common example. Corrosion not only eats away at the material, reducing its cross-section, but it also creates pits and rough surfaces. These pits act as perfect stress risers, making the shaft much more susceptible to fatigue failure. A shaft that might last for years in a dry environment could fail in months in a wet or chemical-laden one.

4. Plastic Deformation (Overload)

This type of failure is more straightforward. It happens when the shaft is subjected to a single, sudden load that exceeds the material’s yield strength. This could be from a machine jam, a sudden impact, or a major operational error. The result is a permanent bend or twist in the shaft. While the shaft may not have broken completely, it’s often unusable. A bent shaft will cause severe vibrations, damage bearings and seals, and throw the entire system out of alignment.

| Failure Mode | Primary Cause | Key Visual Indicators |

|---|---|---|

| Fatigue Fracture | Cyclic loading, stress concentrations | "Beach marks" on fracture surface, sudden final fracture |

| Wear | Friction, contamination, poor lubrication | Scratches, grooves, loss of dimension, polished areas |

| Corrosion | Environmental exposure (moisture, chemicals) | Rust, pitting, discoloration |

| Plastic Deformation | Single event overload exceeding yield strength | Permanent bending, twisting, or visible distortion |

What are the specific failure modes of drive shafts?

Drive shafts are a special case. They don’t just hold things; they transmit torque at high speeds, often across changing angles. A failure here is not just a breakdown; it can be a violent, dangerous event, especially in a vehicle or a piece of heavy machinery. So, what makes them fail?

Drive shafts fail due to torsional fatigue from fluctuating torque, universal joint (U-joint) or constant-velocity (CV) joint failure, and dynamic imbalance. These issues are specific to their role in transmitting power between distant components, making them vulnerable to vibrations and high twisting forces.

I once worked with a client who operated a fleet of mining trucks. They were experiencing repeated drive shaft failures that were causing massive downtime. The problem wasn’t the shaft material itself, but a combination of factors unique to their application. Let’s break down these specific failure modes.

Torsional Fatigue

While any shaft can experience fatigue, drive shafts are uniquely susceptible to torsional fatigue. This is a fracture caused by repeated twisting loads. Every time a driver accelerates or the load on a machine changes, the torque sent through the drive shaft fluctuates. These cycles of twisting and untwisting put stress on the shaft. Just like with bending fatigue, cracks can form at stress risers like splines or welds. The fracture surface often shows a star-like pattern originating from the center or a shear-type failure at a 45-degree angle, which is characteristic of torsional stress.

Universal Joint (U-joint) or CV Joint Failure

U-joints and CV joints are the critical components that allow a drive shaft to transmit power at an angle. They are also a common point of failure. The needle bearings inside a U-joint require clean and consistent lubrication. If a seal fails, grease escapes, and contaminants like water and dirt get in. This quickly leads to wear, corrosion, and eventual seizure of the joint. When a U-joint fails, it can cause extreme vibration. In the worst-case scenario, it breaks apart, allowing the drive shaft to drop or flail wildly, causing immense collateral damage. A common sign of a failing U-joint is a clicking or clunking sound when changing direction or a vibration that changes with speed.

Dynamic Imbalance and Critical Speed

Drive shafts rotate at very high speeds. Because of this, they must be perfectly balanced along their entire length. Even a small imbalance—from a manufacturing defect, a thrown balance weight, or even a small dent from a rock—creates a centrifugal force that tries to whip the shaft around. This force increases with the square of the speed, so doubling the speed quadruples the vibration. This vibration fatigues the shaft itself, but it also destroys bearings, seals, and transmission components.

Furthermore, every drive shaft has a "critical speed," a rotational frequency where its natural vibration harmonics are excited, causing it to bow out dramatically in the middle. Operating at or near this speed will lead to rapid failure. This is why long drive shafts are often made in two pieces with a center support bearing.

| Drive Shaft Failure Mode | Primary Cause | Common Symptoms Before Failure |

|---|---|---|

| Torsional Fatigue | Fluctuating engine/motor torque | Often no warning; sudden fracture |

| U-Joint / CV Joint Failure | Lack of lubrication, contamination, wear | Clicking/clunking on turns, squeaking, speed-dependent vibration |

| Dynamic Imbalance | Lost balance weight, shaft damage (dent), defect | Vibration that increases significantly with speed |

What are gear failure modes and how can they be prevented?

Shafts rarely work in isolation; they are usually connected to gears. A problem in the gear system can easily destroy a shaft, and a shaft problem can wreck a gear. If you’re designing a transmission system, you must consider them together. So, how do gears fail?

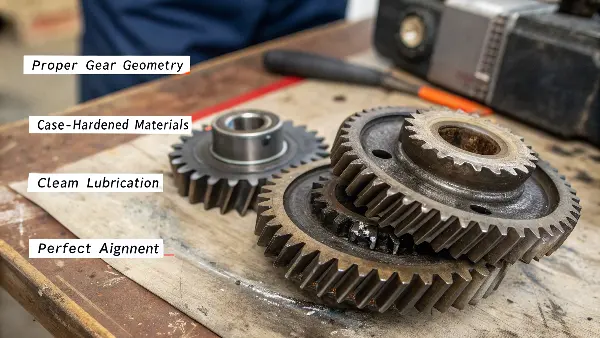

The most common gear failures are tooth fatigue (pitting and fracture), wear, and plastic deformation. These are caused by high contact stresses and sliding friction. Prevention relies on proper gear geometry, selecting materials that can be case-hardened, ensuring clean and adequate lubrication, and maintaining perfect alignment.

Gears are one of the most complex mechanical components to design and manufacture correctly. The forces at play on a tiny gear tooth surface are immense. At QuickCNCs, when we machine gear blanks for customers, we know that the precision of our work is just the first step. The subsequent heat treatment and meshing with other components are just as critical.

Gear Tooth Fatigue

This is the most common mode of gear failure and it comes in two forms:

- Pitting: This is a surface fatigue failure. The high contact pressure between meshing teeth creates microscopic cracks just below the surface. Over time, these cracks grow to the surface, and a small piece of material flakes off, leaving a "pit." Initial micropitting might be acceptable, but as it grows into macropitting, the tooth surface is destroyed, leading to noisy operation and high dynamic loads that can damage the whole system.

- Tooth Bending Fatigue: This is when an entire gear tooth breaks off. A crack initiates at the root of the tooth, where the bending stress is highest. This area is a natural stress concentrator. The crack propagates through the tooth with each load cycle until it fails completely. This is a catastrophic failure that often leads to secondary damage as the broken tooth gets jammed between other gears.

Gear Wear

Wear in gears is the progressive loss of material from the tooth surfaces.

- Abrasive Wear: Caused by hard particles in the lubricant. These contaminants act like a grinding compound, scratching and wearing down the tooth profile.

- Adhesive Wear (Scuffing or Scoring): This is a severe form of wear that happens when the lubricant film between the teeth breaks down under high loads and speeds. The metal surfaces make direct contact, weld together on a microscopic level, and are immediately torn apart. This leaves deep scratches or scoring marks along the direction of sliding.

Plastic Flow

In gears made of softer materials, or under extremely high loads, the tooth surface material can deform without breaking. The pressure literally squeezes the metal, causing it to flow from areas of high contact to areas of low contact. This changes the gear tooth profile, leading to improper meshing, noise, and vibration. It’s often seen as peening or rippling on the tooth surface.

How to Prevent Gear Failure

Preventing these failures is a multi-step process:

- Design and Material: Use proper gear geometry with smooth fillets at the tooth root. Select high-quality alloy steels (like 8620 or 4320) that are suitable for case hardening. This process, like carburizing or nitriding, creates a very hard, wear-resistant surface (the "case") while keeping the inner part of the tooth (the "core") tough and able to absorb shock loads.

- Manufacturing: Precision is key. The tooth profile, surface finish, and spacing must be machined to tight tolerances. Any error will lead to uneven load distribution and premature failure.

- Lubrication: This is absolutely critical. Use the correct type and viscosity of oil, including extreme pressure (EP) additives if needed. Most importantly, keep the oil clean. Filtration and regular oil changes are essential to remove wear particles and contaminants that cause abrasive wear.

How can you actively prevent shaft failure?

We’ve explored all the ways that shafts and gears can fail. It might seem like a lot to worry about. But the good news is that preventing the vast majority of these failures comes down to getting a few key things right at the start. So, what are the most effective strategies?

To prevent shaft failure, focus on a proactive, four-part strategy. First, select the right material and heat treatment for the application. Second, optimize the design to minimize stress concentrations. Third, insist on high-quality manufacturing. Finally, follow strict installation and maintenance procedures.

Thinking about prevention from the very beginning of the design process is the most cost-effective way to ensure reliability. It’s far cheaper to add a fillet radius to a CAD drawing than it is to replace a failed shaft and deal with the associated downtime. Here is the framework I recommend to all the engineers I work with.

1. Smart Material Selection and Heat Treatment

It all starts with the material. You need to balance strength, toughness, and cost.

- Common Materials: For general-purpose shafts, medium carbon steels like 1045 are a good choice. For higher loads, alloy steels like 4140 (chrome-moly) or 4340 (chrome-nickel-moly) offer superior strength and toughness. For corrosive environments, stainless steels like 304 or the much stronger 17-4 PH are necessary.

- Heat Treatment: This is where you customize the material’s properties.

- Through Hardening (Quench and Temper): This strengthens the entire shaft, making it resistant to bending and torsion.

- Case Hardening (Carburizing or Nitriding): This is ideal for shafts that experience high surface wear, like those with integrated gear teeth or bearing journals. It creates a super-hard, wear-resistant outer layer while maintaining a softer, tougher core that can absorb shock without cracking.

2. Design for Durability

How you design the shaft’s geometry is just as important as the material. The goal is to avoid stress concentrations.

- Generous Fillet Radii: A sharp internal corner is the number one enemy of a rotating shaft. Always use the largest possible fillet radius at any step-down in diameter. A small radius can increase stress by a factor of three or more.

- Careful with Keyways and Holes: A standard square keyway creates sharp corners that act as stress risers. A "sled-runner" keyway with a radiused end is much better. If you must drill a hole through the shaft, make sure its edges are chamfered and deburred properly.

- Specify a Smooth Surface Finish: The smoother the surface, the higher the fatigue life. A rough-turned surface is full of microscopic valleys that are perfect starting points for fatigue cracks. Specify a ground or polished finish on critical areas, like where bearings are seated or where the shaft experiences maximum bending stress.

3. High-Quality Manufacturing Matters

Your perfect design is only as good as the company that makes it.

- Precision Machining: Insist on tight tolerances for dimensions like diameter, straightness, and concentricity. A shaft that isn’t straight or round will cause vibrations from day one. This is where partnering with a reliable CNC shop like ours makes a huge difference.

- Finishing and Deburring: Ensure all sharp edges are broken and all burrs are removed. A small burr left in a keyway can create a stress point that leads to failure down the line.

4. Proper Installation and Maintenance

The shaft’s life doesn’t start until it’s installed.

- Precision Alignment: Misalignment between a motor and the machine it drives is a top killer of shafts, bearings, and couplings. Use laser alignment tools for installation; guessing by eye is not good enough.

- Dynamic Balancing: For any shaft that rotates over about 1000 RPM, dynamic balancing is essential to eliminate vibration.

- Clean Lubrication: Use the correct lubricant and stick to a regular schedule for analysis and changes. A good lubrication program is one of the best investments you can make in machine reliability.

| Prevention Strategy | Key Actions | Impact on Reliability |

|---|---|---|

| Material & Heat Treatment | Match material to load/environment; apply case or through hardening. | Increases strength, toughness, and wear/corrosion resistance. |

| Design for Durability | Use large fillet radii; specify smooth surface finish; design better keyways. | Drastically reduces stress concentrations and increases fatigue life. |

| Quality Manufacturing | Hold tight tolerances; ensure proper deburring and finishing. | Prevents built-in flaws, ensures proper fit and balance. |

| Installation & Maintenance | Use laser alignment; perform dynamic balancing; maintain clean lubrication. | Eliminates external sources of vibration and wear, extending life. |

Conclusion

Proactive design, thoughtful material selection, and diligent maintenance are the keys to reliable transmission shafts. This approach prevents costly downtime and ensures the long-term integrity of your machinery.