Designing parts with carbon fiber can be frustrating. You expect high strength and low weight, but poor machining leads to delamination and costly scrap parts. Following specific design guidelines is the key to avoiding these headaches and getting the performance you need from this advanced material.

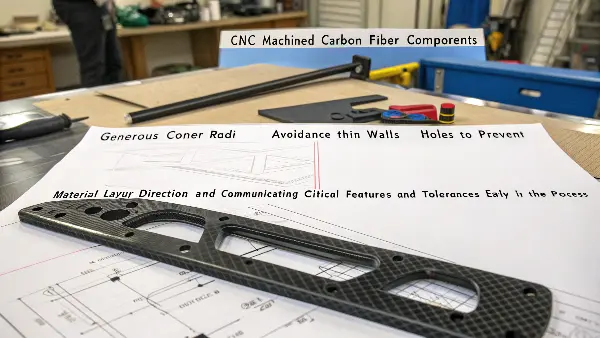

To optimize your design for CNC machined carbon fiber, focus on a few key areas. Use generous corner radii, avoid thin walls, and be mindful of hole placements to prevent material breakout. It is also crucial to understand the material’s layup direction and clearly communicate critical features and tolerances to your machining partner early in the process. These steps will prevent delamination and ensure a high-quality finish.

Over the years, I’ve worked on many projects with engineers like Alex from Germany who need high-performance robotic components. Carbon fiber is often their material of choice, but they quickly learn that designing for it is not like designing for aluminum or steel. Its unique properties demand a different approach. I’ve seen firsthand how small design changes can make a huge difference in the final part’s quality and cost. Let’s walk through the essential guidelines I always share with my clients to help them succeed with their carbon fiber parts.

What Makes Carbon Fiber a Unique Material for CNC Machining?

You know carbon fiber is an amazing material, but do you understand why it behaves so differently on a CNC machine? Its composite nature creates machining challenges that can lead to unexpected failures if you treat it like a simple metal. This can be frustrating and expensive.

Carbon fiber’s uniqueness comes from its structure as a Composite Fiber Reinforced Polymer (CFRP). It is not a uniform material. Instead, it consists of strong, abrasive carbon fibers held together by a softer polymer matrix, like epoxy. This laminated structure makes it highly abrasive and prone to delamination, splintering, and heat damage during machining, unlike isotropic metals which cut predictably.

When I first started machining carbon fiber, I learned some hard lessons. The material doesn’t "chip" away cleanly like aluminum. It "shatters" on a microscopic level. The CNC tool is essentially breaking millions of tiny, hard fibers while cutting through a soft, gummy resin. This dual-action cutting process is what makes it so tricky. It’s not a homogeneous material, where properties are the same in all directions. Instead, it’s anisotropic, meaning its strength and behavior depend on the direction of the fibers.

Anisotropic Properties

The direction of the carbon fiber weave, known as the layup, is critical. A part is much stronger along the fiber direction than it is perpendicular to it. When you design, you have to think about how the cutting forces will interact with these layers. A tool moving parallel to the fibers might produce a clean cut, but a tool cutting across them can easily pull them out of the resin matrix, causing fraying and delamination. This is why communication with your machinist is so important. We need to know which surfaces are cosmetic and which are functional so we can orient the part and plan our toolpaths to minimize stress on the fibers.

Abrasiveness and Thermal Conductivity

The "carbon" in carbon fiber is extremely hard and abrasive—much more so than steel. This wears down standard High-Speed Steel (HSS) and even many carbide tools very quickly. Worn tools generate excess heat and pressure, which are the main causes of delamination. Furthermore, carbon fiber is a poor conductor of heat. Unlike metals that pull heat away from the cutting zone into the workpiece, carbon fiber traps it right at the tool tip. This trapped heat can burn the epoxy resin, weakening the part and causing even more tool wear. This is why specialized tooling and cooling strategies are not just recommended; they are essential for quality results.

What Key Design Features Should You Consider for Carbon Fiber Parts?

Are you struggling to get clean features and tight tolerances on your machined carbon fiber parts? Features that are simple to create in aluminum, like sharp internal corners or closely spaced holes, can become major failure points in carbon fiber, leading to delamination and rejected parts.

For successful carbon fiber part design, prioritize generous internal corner radii (ideally 1.5x the cutter diameter). Avoid walls thinner than 1.5mm and place holes at least 3x the material thickness away from edges. This prevents stress concentrations and delamination. Also, specify countersinks carefully to avoid cutting into the core fibers, which can compromise strength.

I remember working on a drone frame for a client. The initial design had sharp 90-degree internal pockets, just like their previous aluminum version. During the first prototype run, nearly every corner showed signs of delamination and splintering. The sharp change in direction put too much stress on the fiber layers. We revised the design to include a 3mm radius in every internal corner, and the problem disappeared. The parts came out clean, strong, and consistent. This experience highlights how carbon fiber forces you to think differently about feature design. You must design to accommodate the cutting tool’s path and the material’s layered nature.

Internal Radii and Pocketing

Sharp internal corners are the biggest enemy of a good carbon fiber part. A CNC machine uses a round tool, so a perfectly sharp corner is impossible anyway. Trying to get close with a very small tool creates immense stress concentration and heat buildup in the corner, which pulls the layers apart.

- Best Practice: Always design with the largest possible internal radius you can tolerate. A good rule of thumb is a radius of at least 1.0x to 1.5x the cutting tool’s diameter. For a standard 6mm endmill, this means a 6mm to 9mm radius. This allows the tool to move smoothly, reducing cutting forces and leaving a clean, strong corner.

Wall Thickness and Holes

Thin walls and holes placed too close to an edge are other common failure points. The pressure and vibration from the cutting tool can easily cause thin sections to fracture or delaminate.

- Wall Thickness: Aim for a minimum wall thickness of 1.5mm to 2mm. Anything thinner becomes fragile and difficult to machine without specialized support fixtures.

- Hole Placement: Keep holes at least 3x the material thickness away from any edge. For a 3mm thick plate, holes should be at least 9mm from the edge. This provides enough supporting material to prevent "breakout," where the material splinters on the tool’s exit side. For countersunk holes, design them to be shallow enough that the largest diameter doesn’t cut past the top one or two layers of fiber weave.

Which Tools and Machining Parameters Are Best for Carbon Fiber?

Have your machining costs for carbon fiber parts been higher than expected? This is often due to rapid tool wear. Using the wrong tools or machine settings will burn through expensive cutters and can even ruin your workpiece, forcing you to start over with new material.

The best tools for machining carbon fiber are Polycrystalline Diamond (PCD) or diamond-coated carbide endmills and drills. These resist the material’s extreme abrasiveness. Optimal parameters involve high spindle speeds (10,000-20,000 RPM) combined with moderate feed rates. This combination ensures the tool is shearing the fibers cleanly rather than pushing or tearing them, which minimizes heat and prevents delamination.

One of my first big carbon fiber jobs involved producing a series of complex plates for a robotics application. I started with standard carbide endmills, thinking their hardness would be sufficient. I was wrong. The tools were visibly worn after machining just one part, and by the third part, the edge finish was getting rough. I switched to a diamond-coated endmill. The difference was night and day. That single tool lasted for the entire run of 50 parts, and the quality of the cut was consistent from the first piece to the last. This taught me a valuable lesson: investing in the right tooling upfront saves money, reduces scrap, and delivers a better product.

Tooling Material and Geometry

Standard tools don’t stand a chance against carbon fiber. The abrasive fibers act like sandpaper, wearing down the cutting edge almost immediately.

- Polycrystalline Diamond (PCD): This is the ultimate choice for high-volume production. PCD tools have a tip made of synthetic diamond, making them incredibly hard and wear-resistant. They are expensive but offer the longest tool life by far.

- Diamond-Coated Carbide: This is a more cost-effective option for prototyping and small-to-medium production runs. A micro-layer of diamond is deposited over a solid carbide tool. It provides excellent abrasion resistance at a lower price point than PCD.

- Tool Geometry: Special "burr" style or "compression" cutters are ideal. A compression router has up-cutting and down-cutting flutes. This design shears the top and bottom surfaces of the material toward the center, which squeezes the layers together during the cut and dramatically reduces splintering and delamination at the edges.

Speeds and Feeds

Finding the right balance of machine settings is crucial. The goal is to cut the fibers cleanly without generating too much heat.

| Parameter | Recommended Range | Why it Matters |

|---|---|---|

| Spindle Speed (RPM) | High (10,000 – 20,000+) | A high rotational speed ensures a clean shear of the fibers and helps maintain a good surface finish. |

| Feed Rate | Moderate | A moderate feed rate prevents pushing against the material, which causes delamination and excessive tool wear. |

| Depth of Cut | Shallow | Taking smaller passes reduces the cutting force and heat generated, protecting both the tool and the part. |

We achieve the best results by using very high spindle speeds to get a high surface speed at the cutting edge, combined with a feed rate that produces a small, consistent chip. This approach minimizes tool contact time, reduces heat buildup, and leads to a cleaner, faster cut.

How Do You Prevent Delamination and Manage Dust When Machining Carbon Fiber?

Are you consistently seeing frayed edges or separated layers on your finished carbon fiber parts? Delamination is the most common and frustrating defect, while the fine, conductive dust created during machining poses a serious risk to both your equipment and health.

To prevent delamination, use sharp, specialized tooling like compression routers and always support the material with a backer board. Reducing the cutting forces through shallow passes and moderate feed rates is also key. For dust management, a high-volume vacuum system capturing dust directly at the cutting tool is mandatory. This protects machine components and operator health.

I can’t stress the dust issue enough. Early in my career, we machined a batch of carbon fiber parts without a proper dust collection system. The fine black powder got everywhere. A week later, one of our CNC controller boards shorted out. The culprit? Conductive carbon dust had worked its way into the electronics cabinet. It was a costly repair and a huge lesson learned. Now, no carbon fiber job starts in my shop without a dedicated, high-power vacuum shroud directly on the spindle. It’s not just for cleanliness; it’s a critical safety and equipment-preservation measure.

Strategies to Prevent Delamination

Delamination happens when the machining forces pull the layers of carbon fiber apart. This is most common at the entry and exit points of a cut, especially when drilling holes.

- Use a Backer Board: This is the simplest and most effective solution. Placing a sacrificial piece of flat material, like MDF or scrap plastic, underneath your carbon fiber sheet provides support. As the tool exits the carbon fiber, it immediately engages the backer board, preventing the bottom layers from being pushed out and splintering.

- Compression Tooling: As mentioned before, compression routers are designed specifically for this. The opposing helix flutes create a downward force on the top surface and an upward force on the bottom surface, squeezing the material together as it’s being cut. This is highly effective for clean edges on through-cuts.

- Peck Drilling: When drilling holes, instead of pushing the drill through in one motion, we use a "peck drilling" cycle. The drill advances a small amount, retracts to clear chips and reduce heat, and then advances again. This reduces the pressure and heat that cause delamination around holes.

Essential Dust Management

Carbon fiber dust is not something you can ignore. It is sharp, abrasive, and electrically conductive.

- Health Hazard: The fine dust particles can be inhaled and are a serious respiratory irritant. Proper ventilation and personal protective equipment (PPE) like masks are essential for machine operators.

- Equipment Risk: The conductive dust can settle on electronic components like circuit boards and motor windings, causing electrical shorts and equipment failure. It also accelerates wear on the machine’s linear guides and ball screws.

- Solution: The only reliable solution is source capture. A vacuum system with a hose and a "dust shoe" or shroud that surrounds the cutting tool will suck up the vast majority of dust as it’s created, preventing it from ever becoming airborne or settling on the machine.

Conclusion

In summary, successful carbon fiber machining relies on understanding the material, optimizing design features, and using the correct tools and processes to prevent common failures like delamination and tool wear.