Designing a high-performance transmission system is tough. Choosing the wrong material leads to inefficiency, weight issues, and potential failure. This can mean missed deadlines, costly redesigns, and a final product that doesn’t meet performance targets for demanding applications.

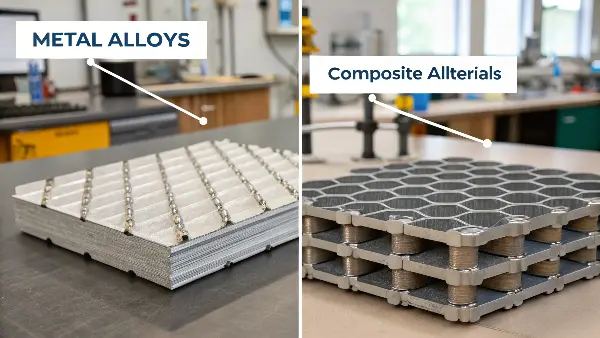

The best material for a transmission shaft depends on your specific goals. Traditional metal alloys like steel and aluminum offer proven strength, isotropic properties, and cost-effectiveness for standard applications. However, advanced composite materials like carbon fiber reinforced polymer (CFRP) provide a superior strength-to-weight ratio, better vibration damping, and immense design flexibility, making them ideal for high-performance and electric vehicles where every gram and decibel matters.

The choice isn’t always clear-cut, and I’ve seen engineers struggle with this decision on countless projects. Both material families have their place in modern engineering, but the trend for cutting-edge applications is undeniably shifting. To make the best choice for your project, you need to look beyond the surface-level specs and understand the fundamental differences in how these materials are structured and how they behave under stress. Let’s break down the details to help you make a truly informed decision for your next design.

What is the fundamental difference between metal alloys and composite materials?

Engineers often discuss metals and composites in the same breath, but their basic structures are worlds apart. This can lead to misapplication, specifying a material that isn’t optimal for the manufacturing process or, worse, for the loads it will face in its service life.

The core difference is in their structure and properties. Metal alloys are monolithic and isotropic, meaning they have a uniform composition and a single set of properties in all directions. Composites are non-monolithic and anisotropic; they are made of distinct materials (like fibers in a resin) and their properties, such as strength and stiffness, can be intentionally directed to handle specific loads.

To really get a grip on this, you have to think about them from the inside out. In my experience helping clients source parts, the most successful projects begin with a deep understanding of the material itself. It’s not just about picking from a list; it’s about knowing why a material behaves the way it does.

The Nature of Metal Alloys

Metal alloys are what most engineers consider the default choice. Think of steel or aluminum alloys. They are created by melting and mixing a primary metal with other elements to enhance properties like strength or corrosion resistance. The result is a material with a uniform crystalline grain structure. This uniformity is key—it means the material is isotropic. If you pull on a piece of aluminum from the top, its response is the same as if you pull on it from the side. This predictability is a huge advantage. It simplifies analysis and makes machining processes, like the CNC turning and milling we manage at QuickCNCs, very reliable. You know exactly what to expect.

The Architecture of Composite Materials

Composites are fundamentally different. They are not a mixture; they are a combination of two or more materials that remain physically separate. Think of it like reinforced concrete—the steel rebar (reinforcement) provides tensile strength, while the concrete (matrix) provides compressive strength and holds everything together. In advanced composites like Carbon Fiber Reinforced Polymer (CFRP), you have extremely strong carbon fibers acting as the reinforcement, held together by a polymer resin matrix. The magic here is that the material is anisotropic. The strength follows the fibers. This means we can design a part to be incredibly strong and stiff in one direction (e.g., along the length of a shaft to resist torsion) while remaining lightweight in other directions. This level of intentional design is something a uniform metal simply cannot offer.

| Feature | Metal Alloys (e.g., 4140 Steel) | Composite Materials (e.g., CFRP) |

|---|---|---|

| Composition | A solid solution of a base metal and other elements. | Two or more distinct materials (reinforcement + matrix). |

| Structure | Monolithic, crystalline grain structure. | Non-monolithic, with fibers or particles embedded in a matrix. |

| Properties | Isotropic (uniform properties in all directions). | Anisotropic (properties are directional, depend on fiber layout). |

| Failure Mode | Typically ductile, showing deformation before breaking. | Often brittle, with little warning before catastrophic failure. |

| Manufacturing Insight | Well-understood for machining, forging, and casting. | Requires specialized processes like filament winding or lay-up. |

This distinction is the foundation for every other comparison we’ll make. One is predictably uniform, and the other is directionally brilliant.

Are composites really considered advanced materials?

The term "advanced material" gets thrown around a lot in marketing. Does it just mean it’s new, or is there a more concrete engineering definition? Using a material you don’t fully understand can be risky, especially if you’re paying a premium without a clear performance benefit.

Yes, composites are unequivocally advanced materials. Their "advanced" status comes not from being new, but from being intentionally engineered at a microscopic level. They are designed to achieve specific, combined performance characteristics—like high stiffness and low density—that are impossible to find in any single, monolithic material like a metal or a ceramic.

Over my career, I’ve seen the term used loosely for many things. But when it comes to composites, it’s a perfect fit. The difference between a simple material and an advanced one is the level of human design and intent embedded within its very structure.

Beyond Simple Mixtures: The Engineering Aspect

An alloy, like brass, is a mixture of copper and zinc. The elements combine at an atomic level to form a new material with its own set of uniform properties. A composite, on the other hand, is a team of materials working together. The fibers and the matrix never lose their individual identities; they are strategically combined so the final product gets the best properties of each. This is not a simple mixture; it’s a structural system designed at the micro-scale. I once worked with a client designing a high-speed robotic arm. The aluminum design was light, but it would oscillate after a fast movement, ruining precision. We switched to a carbon fiber composite arm. By designing the layup of the carbon fibers, we created an arm that was just as light but incredibly stiff and damped vibrations almost instantly. That’s the difference between picking a material off a shelf and designing the material itself.

Tailored Performance on Demand

The true hallmark of an advanced material is the ability to tailor its properties. With composites, an engineer can decide exactly where the strength should be. For a transmission shaft, the primary load is torsion. We can orient the carbon fibers at a ±45-degree angle to the shaft’s axis to best resist this twisting force. If there’s also a bending load, we can add fibers oriented at 0 degrees along the length. This process, called ply design or layup scheduling, gives the designer incredible control. You can tune stiffness, strength, thermal expansion, and even vibrational frequency response. This is a level of design freedom that is simply unimaginable with an isotropic metal, where you are stuck with the same properties in every direction, whether you need them or not.

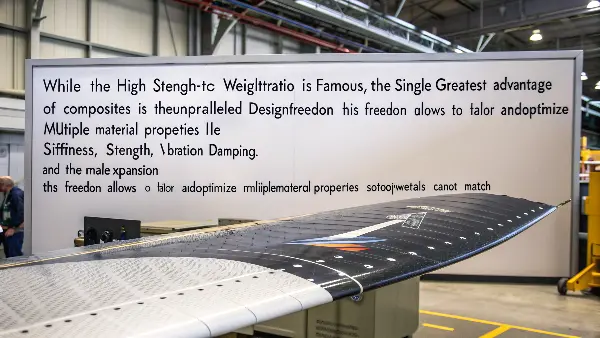

What is the single biggest advantage that composites have over other materials?

Everyone knows composites are lightweight. But if you see that as their only defining feature, you’re missing the bigger picture. Focusing only on weight reduction means you might overlook other critical benefits that could solve complex engineering challenges that metals can’t touch.

While the high strength-to-weight ratio is famous, the single greatest advantage of composites is the unparalleled design freedom they offer. This freedom allows engineers to tailor and optimize multiple material properties—like stiffness, strength, vibration damping, and thermal expansion—directionally within a single component. This lets you build a part that is optimized for its specific job in a way isotropic metals cannot match.

This design freedom manifests in several practical, game-changing benefits. From my vantage point managing CNC projects, I see engineers solve problems with composites that had them stumped for years with metals. It’s not just about making something lighter; it’s about making it smarter.

The Unbeatable Strength-to-Weight Ratio

Okay, let’s start with the most obvious benefit because it is still incredibly important. A material’s performance is best measured by its specific strength (strength divided by density) and specific modulus (stiffness divided by density). On these metrics, composites like CFRP are in a class of their own. For example, high-end CFRP can offer the same tensile strength as high-strength steel at only about 20% of the weight. For a transmission shaft, this means reducing rotational inertia. A lighter shaft can spin up and slow down faster, improving the vehicle’s acceleration, responsiveness, and overall efficiency, whether it’s consuming fuel or battery power. This is not an incremental improvement; it’s a leap forward.

Superior Damping and Fatigue Resistance

This is a huge advantage, especially for transmission shafts. Every rotating system produces vibrations, which create noise and wear. Metals, with their rigid crystalline structure, are very good at transmitting these vibrations. A steel shaft can act like a bell, ringing with noise from the gearbox. A composite shaft, however, behaves differently. The polymer matrix in the composite is viscoelastic, meaning it can absorb and dissipate vibrational energy as a tiny amount of heat. This "damping" effect leads to a massive reduction in Noise, Vibration, and Harshness (NVH). Furthermore, composites don’t fatigue like metals. Metals accumulate micro-cracks under cyclic loading, which eventually lead to failure. Composites, particularly CFRP, have exceptional fatigue resistance, leading to a longer and more reliable service life under punishing conditions.

| Property | 4140 Steel | 6061-T6 Aluminum | Carbon Fiber (CFRP) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Density (g/cm³) | ~7.85 | ~2.70 | ~1.60 |

| Specific Strength | Medium | Medium-High | Very High |

| Specific Stiffness | Medium | Medium | Very High |

| Vibration Damping | Poor | Poor | Excellent |

| Fatigue Resistance | Good (but has a defined limit) | Fair | Excellent |

| Corrosion Resistance | Poor (Requires coating) | Good | Excellent |

This combination of properties, all stemming from that initial design freedom, is what makes composites so powerful.

Why are composites becoming the preferred material for automotive transmission shafts?

For a hundred years, steel driveshafts have been the standard. They are strong, cheap, and reliable. So why change what seems to work perfectly well? Sticking with old technology in the era of electric vehicles and high-efficiency engines means falling behind on performance, range, and refinement benchmarks.

Composites are becoming preferred for modern transmission shafts for two primary reasons related to weight and dynamics. First, their low weight reduces rotational inertia, which directly improves acceleration and efficiency. Second, their high specific stiffness allows for longer, single-piece shafts that can operate at higher rotational speeds without vibrating, eliminating the need for a failure-prone center bearing assembly.

This isn’t just a theoretical benefit. At QuickCNCs, we’ve worked on prototypes for several EV startups and high-performance racing teams. The shift to composites is a direct response to tangible engineering problems that steel and aluminum can no longer solve effectively.

Meeting the Demands of Electric Vehicles (EVs)

In an internal combustion engine car, a heavy driveshaft is just one of many heavy components. In an EV, where every gram of weight is scrutinized to maximize battery range, a heavy steel shaft is a liability. Reducing the driveshaft’s weight by 50-70% by switching to CFRP has a direct impact on range and performance. Furthermore, EVs deliver instant torque from 0 RPM. This puts immense stress on the drivetrain. A composite shaft can be designed to have a specific torsional stiffness, acting as a slight "cushion" during aggressive acceleration, protecting the gearbox while still delivering exceptional responsiveness. In the silent cabin of an EV, drivetrain noises like gear whine become much more apparent. The superior damping of a composite shaft is critical for absorbing this noise and delivering the quiet, premium experience EV buyers expect.

Solving Critical Speed and NVH Challenges

This is perhaps the most elegant engineering reason for the switch. Any long, spinning shaft has a "critical speed"—a rotational speed at which it begins to flex and whip like a jump rope. To avoid this, long steel driveshafts must be made in two pieces, connected by a center support bearing. This bearing, however, is a common point of failure and a source of vibration and noise. Because composite shafts have such high specific stiffness (they are very stiff for their low weight), their critical speed is much higher. This allows engineers to design a single, long driveshaft that can span the entire distance from the transmission to the differential without needing a center bearing. This simplifies the entire assembly, removes a failure point, reduces part count and cost, and dramatically lowers overall system NVH. It’s a cleaner, more efficient, and more reliable solution.

Conclusion

Ultimately, while metal alloys remain reliable workhorses, composites offer tailored performance for modern challenges. For high-performance transmission shafts, their lightweight strength and dynamic benefits are driving the future of automotive design.