Choosing between machined and cast aluminum seems like a simple cost decision. But picking the wrong one can lead to hidden expenses, redesigns, and even product failure down the line. Understanding the Total Cost of Ownership (TCO) reveals the true, long-term cost of your choice.

The true cost depends on volume and complexity. Casting is cheaper for high-volume production due to low per-part costs, despite high initial tooling expenses. CNC machining is more cost-effective for low-volume, high-precision, or complex parts, as it avoids tooling costs and offers superior material properties. The total cost of ownership considers factors beyond just the initial price.

It’s a question I get all the time from engineers like Alex. They see a quote for a machined part and a quote for a cast part, and the numbers look very different. But the initial price tag is just the first chapter of the story. To make the right decision for your project, you need to read the whole book. Let’s start by tackling the most common question first.

Is Casting or Machining More Expensive Upfront?

You have two quotes, one for casting and one for machining, and the price difference is huge. Choosing based on the per-piece price alone could lock you into a process that’s not right for your volume or design. Let’s break down where the costs come from.

Initially, casting is more expensive for small quantities due to high tooling (mold) costs, which can be thousands of dollars. Machining has no tooling costs, making it cheaper for prototypes and low-volume runs. For mass production, casting becomes cheaper per part, as the tooling cost is spread across thousands of units. Machining costs per part remain relatively constant.

The upfront cost is the most visible difference between these two methods. It’s also the most misleading if you don’t look deeper. I remember a client who needed 200 enclosures for a new electronics device. They were focused on getting the lowest possible per-unit price and immediately leaned toward die casting. The per-unit quote was indeed attractive, but it came with a $10,000 tooling fee. For their run of 200 units, that added $50 to the cost of every single part, making it far more expensive than CNC machining. We showed them the math, and they quickly switched to machining, saving thousands of dollars on that initial batch.

The High Initial Hurdle of Casting: Tooling Costs

The main cost driver for casting is the mold, also called a tool or die. Creating this hardened steel mold is a precise and expensive process. The cost can range from a few thousand dollars for a simple design to tens of thousands for a complex one. This is a fixed, one-time cost you must pay before a single part is produced. This investment only makes sense if you can spread that cost over a very large number of parts, typically thousands or tens of thousands.

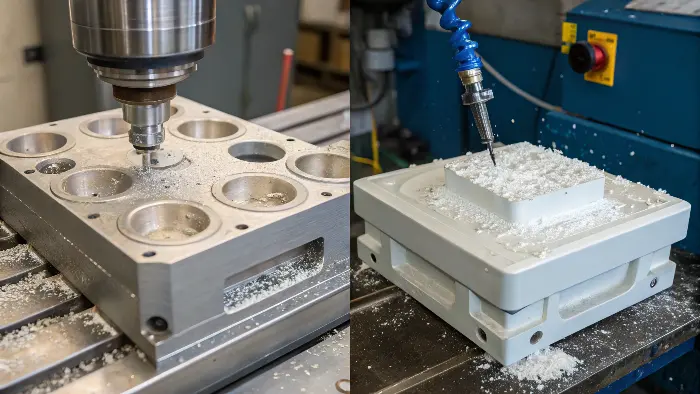

The Pay-As-You-Go Model of CNC Machining

CNC machining works differently. There are no tooling costs. We take your CAD file, program the machine, and cut your part directly from a solid block of metal. The cost is based on machine time, material, and labor for each part. This means the price per part stays relatively consistent whether you order one, one hundred, or one thousand pieces. This "pay-as-you-go" model makes it ideal for prototyping, low-volume production, and situations where the design might change.

Finding the Break-Even Point

The key is to calculate the break-even point. This is the number of parts you need to produce for the total cost of casting (tooling + cost per part) to equal the total cost of machining.

| Cost Factor | CNC Machining | Die Casting |

|---|---|---|

| Tooling Cost | $0 | $5,000 – $50,000+ |

| Per-Part Cost | Relatively High | Very Low |

| Best for Volume | Low (<500 parts) | High (>1000 parts) |

| Lead Time | Fast (Days/Weeks) | Slow (Months for tooling) |

For any engineer, calculating this break-even point is the first step in making a sound financial decision.

How Strong is Cast Aluminum Compared to Machined Aluminum?

You’ve saved money with casting, but now you’re worried about performance. A part that fails under stress can cause catastrophic damage, costly recalls, and ruin your company’s reputation. Understanding the material differences is key to ensuring reliability.

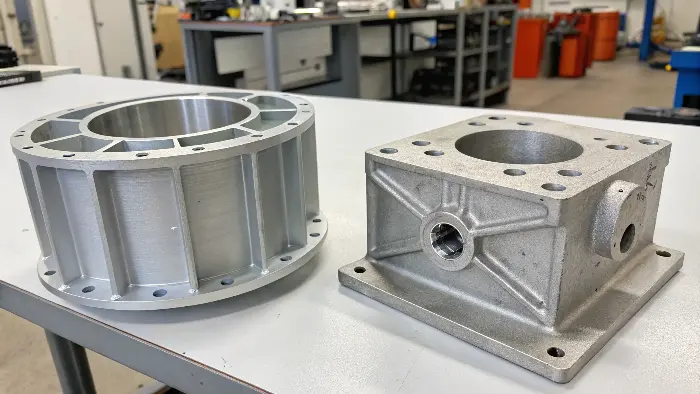

Machined aluminum is significantly stronger and more durable than cast aluminum. Machining starts with a solid block of wrought aluminum (like 6061-T6), which has a uniform, non-porous grain structure. Casting involves molten metal, which can introduce porosity, voids, and inconsistencies. This makes cast parts more brittle and less resistant to fatigue and impact.

The difference in strength isn’t just a small detail; it’s fundamental to how the materials are formed. Think of it like the difference between a natural diamond and a synthetic one made by pressing carbon dust together. One is formed under immense, uniform pressure over time, creating a perfect crystal structure. The other is fused together, leaving microscopic gaps and weaknesses.

The Grain Structure Advantage of Machined Parts

CNC machining starts with a billet of wrought aluminum, like the very common 6061-T6 or the high-strength 7075-T6. These billets have been extruded or rolled, a process that aligns and elongates the grain structure of the metal. This gives the material incredible tensile strength and fatigue resistance. When we machine a part, we are simply carving away material, leaving this superior internal structure intact.

Porosity: The Hidden Weakness of Casting

Casting, on the other hand, involves pouring molten aluminum into a mold. As the metal cools and solidifies, tiny gas bubbles can get trapped, creating microscopic voids called porosity. These pores act as stress concentrators. When the part is put under load, cracks can start at these weak points and spread, leading to failure at a much lower force than a solid, machined part could withstand. While techniques exist to minimize porosity, it can never be completely eliminated.

When is Cast Strength "Good Enough"?

This doesn’t mean cast parts are useless. For many applications, their strength is perfectly adequate. I worked with a client who was designing a desktop instrument housing. The part was not structural; its job was to protect the internal electronics and look good. For this, a cast A380 aluminum part was the perfect choice. It was cost-effective at their high volume, and its mechanical properties were more than sufficient. The key is to match the material’s properties to the application’s demands. For a structural bracket on a robot arm, I would always recommend machined aluminum. For a decorative cover, casting is often the smarter choice.

| Property | Machined (6061-T6) | Cast (A380) |

|---|---|---|

| Tensile Strength | ~310 MPa | ~324 MPa* |

| Yield Strength | ~276 MPa | ~165 MPa |

| Fatigue Strength | ~96 MPa | ~35 MPa |

| Structure | Uniform, non-porous | Can have porosity |

*Note: While A380’s ultimate tensile strength looks similar, its low yield and fatigue strength show it will deform and fail under repeated stress much sooner than 6061-T6.

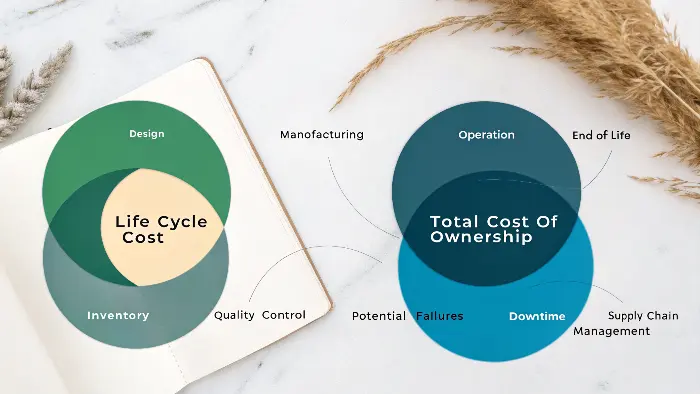

What’s the Difference Between Life Cycle Cost and Total Cost of Ownership?

You hear terms like "Life Cycle Cost" (LCC) and "Total Cost of Ownership" (TCO) thrown around. They sound similar, but confusing them can lead to an incomplete analysis of your project’s true financial impact. Let’s clarify the distinction and see why TCO is the better metric.

Life Cycle Cost (LCC) typically focuses on the direct costs associated with a part from creation to disposal: design, manufacturing, operation, and end-of-life. Total Cost of Ownership (TCO) is a broader concept. It includes all LCC elements plus indirect and hidden costs like inventory, quality control, potential failures, downtime, and supply chain management.

Thinking about TCO is what separates good engineers from great ones. A good engineer can find a low-cost part. A great engineer, like my client Alex, understands that the part’s price is just one piece of a much larger puzzle. He knows that a cheap part that fails in the field can cost his company ten times the initial savings in warranty claims, reputational damage, and lost sales.

Life Cycle Cost: The Direct Financial Path

Life Cycle Cost is the straightforward accounting of a part’s journey. It includes:

- Design & Development: The engineering hours spent creating the part.

- Production: The cost of tooling and manufacturing each unit.

- Operation: Any energy or maintenance costs associated with the part during its use.

- Disposal: The cost to recycle or dispose of the part at the end of its life.

LCC is a good start, but it misses many of the real-world business costs.

Total Cost of Ownership: The Bigger Picture

TCO includes everything in LCC, but adds the critical "hidden" costs. When comparing machined vs. cast parts, TCO forces you to ask better questions:

- Quality & Inspection: Will cast parts require more extensive inspection (like X-rays) to check for porosity? What is the cost of that extra labor and equipment?

- Failure & Downtime: What is the financial impact if a weaker cast part fails and shuts down a customer’s production line?

- Inventory: Does casting require a large Minimum Order Quantity (MOQ), forcing you to hold and manage expensive inventory? Machining allows for smaller, just-in-time orders.

- Supply Chain Risk: What is the cost of a longer lead time for casting? Does it make your supply chain less agile and responsive to changes in demand?

Why TCO Matters for Engineers

By using a TCO framework, an engineer can make a much stronger case for their manufacturing choice. Instead of just saying, "The machined part is more expensive," they can say, "The machined part has a higher unit price, but it eliminates the risk of field failure, reduces our inventory costs by $15,000, and allows us to respond to design changes in days instead of months. Its Total Cost of Ownership is actually lower." This is the kind of analysis that saves companies real money.

What Should You Consider When Choosing Between Casting and Machining?

You understand the individual differences between casting and machining. But now you have to weigh all these factors—cost, strength, volume, complexity—for your specific project, and it feels overwhelming. Here is a practical checklist to guide your decision.

The key considerations are production volume, part complexity, material requirements, and dimensional tolerances. Casting is best for high volumes (>1000 units) of simpler parts where lower strength is acceptable. Machining excels at low-to-mid volumes, complex geometries, tight tolerances (better than ±0.1mm), and applications demanding high-strength materials.

Making the final call requires a balanced view of your project’s specific needs. There is no single "best" method; there is only the "best" method for your application. I often walk my clients through a decision matrix to bring clarity to this choice. It helps organize the trade-offs and highlights the most important factors for their project.

The Decision Matrix: A Practical Guide

Here is a simple table you can use to evaluate your part against the strengths and weaknesses of each process.

| Factor | Best for CNC Machining | Best for Casting |

|---|---|---|

| Production Volume | Low to Medium (1 – 1000+) | High to Very High (1000+) |

| Part Complexity | High (undercuts, thin walls, complex surfaces) | Medium (simpler forms, draft angles required) |

| Dimensional Tolerance | Very Tight (±0.01mm is possible) | Moderate (±0.1mm is typical) |

| Surface Finish | Excellent (can be very smooth, Ra < 1.6μm) | Good (texture from the mold, requires secondary finishing) |

| Material Strength | Excellent (uses high-strength wrought alloys) | Good (lower strength due to process) |

| Lead Time | Fast (days to weeks) | Slow (months for tooling) |

| Design Flexibility | High (easy and cheap to change the CAD file) | Low (changes require expensive mold modification) |

Weighing Volume Against Complexity

This is often the central trade-off. Casting can produce very complex shapes, but CNC machining can produce shapes that are impossible to cast, such as parts with internal undercuts or features that lack a draft angle. I once worked on a manifold for a hydraulic system. The internal channels were so intricate that it could only be made by machining it in two halves and then brazing them together. Casting was not an option, regardless of the volume.

The Importance of Tolerances and Finish

If your part needs to fit perfectly with other components, or if it requires a very smooth surface for sealing or aesthetic reasons, CNC machining is almost always the superior choice. Casting tolerances are generally an order of magnitude looser than what machining can achieve. While cast parts can be post-machined to improve tolerance in critical areas, this adds another step and more cost to the process, reducing the initial cost advantage of casting. For engineers like Alex, who regularly work with tolerances of ±0.01mm, CNC machining is the only viable path.

Conclusion

The choice between machined and cast aluminum isn’t just about the initial price. It’s a strategic decision based on your project’s entire lifecycle. By considering volume, strength, complexity, and the total cost of ownership, you can choose the method that delivers true long-term value and success.