Struggling to get clean, precise grooves in titanium parts? This tough material can quickly wear out your tools and ruin expensive components, causing project delays. The fear of a failed groove on a mission-critical aerospace part is a serious concern for any engineer or machinist.

Mastering titanium grooving requires using sharp, positive rake inserts with a specific PVD coating like TiAlN. You need a rigid machine setup, low cutting speeds (30-60 m/min), and a high-volume, high-pressure coolant supply directed at the cutting edge. This combination minimizes heat buildup, prevents work hardening, and ensures clean chip evacuation for precise grooves and excellent surface finish.

I’ve spent years working with aerospace clients, and titanium is a material we handle almost every day. The challenges are real, but so are the rewards when you get it right. Before we get into the nitty-gritty of grooving techniques, it helps to understand why titanium is so essential in the first place. This context makes the machining challenges much clearer. Let’s explore why this metal has become a star player in the aerospace world.

Why Is Titanium the Go-To Metal for the Aerospace Industry?

Choosing the right material for an aerospace component is a huge decision. You are constantly balancing the need for strength and durability against the urgent need to reduce weight. The wrong choice could mean lower fuel efficiency, reduced payload, or even structural failure under extreme conditions.

Titanium is the go-to metal for the aerospace industry because of its phenomenal strength-to-weight ratio. It’s as strong as many steels but around 45% lighter. It also has excellent corrosion resistance and can withstand the extreme temperatures found in high-performance engines and airframes, making it an ideal material for building safer, lighter, and more efficient aircraft.

Throughout my career, I’ve seen countless drawings from engineers like Alex in Germany where titanium is specified for parts that will face hellish conditions. Its unique combination of properties makes it nearly irreplaceable. It’s not just one thing; it’s a package of benefits that no other commercially available metal can offer in the same way. Let’s break down exactly what makes it so valuable.

The Unbeatable Trio: Strength, Weight, and Temperature Resistance

The primary driver for titanium’s use is its efficiency. In an industry where every gram counts, titanium delivers incredible performance without the weight penalty of steel.

- Strength-to-Weight Ratio: This is the most famous benefit. A component made from a titanium alloy like Ti-6Al-4V can provide the same structural integrity as a steel part while weighing almost half as much. This translates directly to increased fuel efficiency, longer range, or a higher payload capacity.

- High-Temperature Performance: Aluminum alloys, while lightweight, lose their strength rapidly as temperatures climb above 150°C (300°F). Titanium, on the other hand, retains its strength at temperatures up to 600°C (1100°F). This makes it essential for parts near the engine or on leading edges that experience high friction.

The Unseen Protector: Corrosion Resistance

I remember a project for a client who needed parts for a landing gear assembly. The components would be exposed to de-icing fluids, saltwater spray, and extreme weather. Steel would have required heavy protective coatings, adding weight and maintenance costs. We used titanium, and its natural passive oxide layer provided all the protection needed. This layer, which forms instantly when exposed to air, makes titanium virtually immune to corrosion from seawater, industrial chemicals, and other harsh environments.

Here’s a simple table comparing these key properties:

| Property | Aluminum Alloy (7075-T6) | Steel (4130) | Titanium Alloy (Ti-6Al-4V) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Density (g/cm³) | 2.81 | 7.85 | 4.43 |

| Tensile Strength (MPa) | ~570 | ~670 | ~950 |

| Strength-to-Weight Ratio | High | Medium | Very High |

| Max Service Temp. | ~150°C | ~400°C | ~600°C |

| Corrosion Resistance | Moderate (needs coating) | Low (needs coating) | Excellent (passive layer) |

This combination of properties explains why titanium isn’t just a choice; it’s often the only choice for parts that need to be light, strong, and durable in the most demanding conditions imaginable.

What Are the Critical Applications of Titanium in the Aerospace Industry?

You know titanium is strong and light, but where does it actually get used? It’s one thing to know the theory, but seeing the real-world applications helps you understand the stakes. A failure in one of these parts isn’t just an inconvenience; it can be catastrophic.

Titanium’s critical applications are concentrated in areas with high stress and high temperatures. This includes jet engine components like fan blades, discs, and compressor parts. It’s also used in structural airframe components like landing gear beams, wing supports, and critical fasteners, where strength, fatigue resistance, and low weight are absolutely essential for safety and performance.

When an order for a set of Ti-6Al-4V engine mounts comes across my desk, the level of precision required is immense. These aren’t just simple brackets; they are the connection point holding a multi-million dollar engine to the wing. There is zero room for error. The material choice reflects that reality. Let’s look closer at where this metal proves its worth.

The Heart of the Aircraft: Engines

Jet engines are the most intense environment on an airplane. Inside, you have incredible forces, extreme temperatures, and a constant demand for reliability.

- Fan Blades and Discs: The front section of a modern turbofan engine is dominated by large fan blades. These are often made from titanium alloys because they need to be strong enough to withstand bird strikes while being light enough to spin at thousands of RPM without creating excessive stress on the engine hub.

- Compressor Components: As air moves deeper into the engine, it gets compressed and heated. The blades and discs in the initial stages of the compressor are made of titanium because aluminum would fail at these temperatures, and steel would be too heavy.

The Bones of the Aircraft: Airframe

The airframe is the skeleton of the plane. It must carry all the loads during flight, from the wings lifting the fuselage to the landing gear absorbing the impact of touchdown.

- Landing Gear: This is a perfect example of a high-stress application. Landing gear beams must be incredibly strong to handle the forces of landing without fracturing. Using titanium instead of steel saves hundreds of kilograms, improving the aircraft’s overall efficiency.

- Wing Structures: The internal "wing box" or the spars that run the length of the wing are often made of titanium. This is especially true in military aircraft where the wings must endure extreme G-forces during maneuvers.

- Fasteners and Seat Rails: Even small parts matter. Thousands of high-strength fasteners holding the aircraft together are made from titanium. They offer the strength of steel at a fraction of the weight and won’t corrode. The rails that hold passenger seats are also often titanium for the same reasons.

Here is a breakdown of common titanium usage by aircraft section:

| Aircraft Section | Key Components | Reason for Titanium Use | Common Alloy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Engine | Fan blades, compressor discs, casings | High temp. strength, fatigue resistance, low density | Ti-6Al-4V, Ti 8-1-1 |

| Airframe | Landing gear beams, wing spars, pylons | High strength-to-weight ratio, fracture toughness | Ti-6Al-4V, Ti-10-2-3 |

| Nacelle | Exhaust cones, "hot" structures | High-temperature resistance, acoustic properties | Commercially Pure (CP) Ti |

| Systems | Hydraulic tubing, fasteners, springs | Corrosion resistance, high strength, formability | Ti-3Al-2.5V, Beta-C |

Each of these applications pushes the boundaries of manufacturing. They require complex shapes, tight tolerances, and a deep understanding of how to machine this challenging material—which brings us back to the core challenge of grooving.

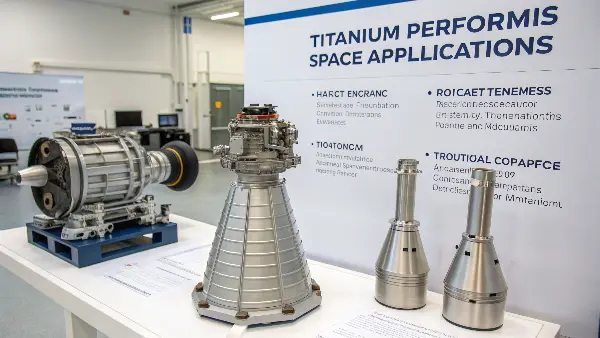

How Does Titanium Perform in Space Applications?

Moving beyond Earth’s atmosphere, the challenges intensify. You face extreme temperature swings, a hard vacuum, and intense radiation. Materials that work perfectly on an airplane might fail spectacularly in space. So how does our wonder metal, titanium, hold up when we leave the planet?

In space applications, titanium is highly valued for its ability to withstand extreme temperature variations, from cryogenic cold to high heat. Its low thermal expansion, high strength, and excellent corrosion resistance make it ideal for rocket engine components, pressure vessels, and structural elements on satellites and spacecraft that must operate reliably in a vacuum without degrading.

I once had the opportunity to machine a few prototype components for a satellite project. The parts were propellant tanks. The client’s main concerns were preventing leaks under high pressure and ensuring the material wouldn’t become brittle at the cryogenic temperatures of liquid fuel. Titanium was the only material on their list that could meet both demands.

Surviving the Extremes of Space

The environment outside our atmosphere is unforgiving. A material must perform flawlessly across a massive temperature range.

- Cryogenic Performance: Many spacecraft use liquid hydrogen and oxygen as propellants, stored at incredibly cold temperatures (-253°C and -183°C, respectively). While many metals become brittle and fracture at these temperatures, certain titanium alloys actually maintain or even improve their strength and ductility. This makes them perfect for building lightweight and reliable propellant tanks, fuel lines, and engine valves.

- Thermal Stability: As a satellite orbits the Earth, it moves from direct sunlight to complete shadow, causing temperatures to swing by hundreds of degrees. Materials expand and contract with these changes. Titanium has a relatively low coefficient of thermal expansion, meaning it changes size less than other metals. This stability is critical for sensitive instruments and structures like antennas and sensor mounts that need to maintain their precise shape.

Building Rockets and Spacecraft

From launch to long-duration missions, titanium is a key enabler.

- Rocket Engines: The combustion chambers and nozzles of rocket engines face unimaginable heat and pressure. Specialized titanium alloys are used in these areas for their high-temperature strength and resistance to erosion from hot gases. The entire structure of some upper-stage engines is made of titanium to save weight, allowing for larger payloads.

- Pressure Vessels: Besides fuel tanks, spacecraft use high-pressure vessels to store helium and other gases for attitude control systems. Ti-6Al-4V is a standard choice for these spheres and cylinders because it can be made into thin-walled, lightweight tanks that are strong enough to contain gases at thousands of PSI.

- Structural Frameworks: The internal lattice or frame of a satellite is often built from titanium tubing. This provides a strong, rigid skeleton to mount all the electronics and scientific instruments without adding unnecessary mass.

This table shows how titanium’s properties align with the needs of space exploration:

| Space Application Requirement | How Titanium Meets the Need | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Operation in vacuum | Does not outgas; maintains structural integrity | All space components |

| Cryogenic temperatures | Remains ductile and strong, does not become brittle | Liquid fuel tanks (e.g., SpaceX Starship) |

| High temperatures | Retains strength under engine heat or solar radiation | Rocket engine nozzles, heat shields |

| Low launch mass | Excellent strength-to-weight ratio reduces launch costs | Satellite frames, pressure vessels |

| Dimensional stability | Low thermal expansion keeps instruments aligned | Telescope structures, antenna mounts |

The use of titanium in space highlights its ultimate reliability. When you can’t send a technician to fix something, you choose a material that you know will not fail.

What Are the Disadvantages of Titanium in Aerospace?

We’ve talked a lot about why titanium is so great. But if it were perfect, we’d build everything out of it. The reality is, that titanium has significant disadvantages that create major challenges. These drawbacks are the very reason why specialized knowledge in machining it is so valuable.

The main disadvantages of titanium are its high cost and extreme difficulty in machining. The raw material is expensive to produce, and its properties—low thermal conductivity and high chemical reactivity—cause rapid tool wear, poor chip control, and work hardening during machining. This makes manufacturing titanium parts a slow, costly, and technically demanding process.

This is the part of the process where I spend most of my time: solving the problems caused by titanium’s difficult nature. An engineer might design the perfect part, but if it can’t be manufactured affordably and reliably, the design is useless. The cost and manufacturability are the two biggest hurdles we have to overcome.

The High Cost of Performance

Titanium isn’t a metal you just dig out of the ground in a pure state.

- Extraction and Processing: The Kroll process, the primary method for producing titanium metal from its ore, is a multi-stage, energy-intensive batch process. It’s far more complex and expensive than the simple smelting used for iron. This makes the raw material 5 to 10 times more expensive than aluminum and significantly more than specialty steels.

- Scrap Value: Because titanium is so reactive, scrap from machining can’t be easily re-melted and reused like aluminum. It has to be carefully segregated by alloy and requires special processing, so its reclaim value is lower. This means wasted material is a major cost driver.

The Machinist’s Nightmare: Manufacturing Challenges

This is where we return to our main topic: grooving and other machining operations. Titanium fights you every step of the way.

- Low Thermal Conductivity: When you cut metal, you generate heat. With aluminum or steel, that heat is carried away in the chip. Titanium is a poor thermal conductor, so the heat stays concentrated at the cutting tool’s edge. This leads to extremely high temperatures that can soften, deform, or even melt the cutting insert.

- Galling and Chemical Reactivity: At the high temperatures and pressures of cutting, titanium chips tend to weld themselves to the tool tip. This is called galling or built-up edge (BUE). It destroys the cutting edge, ruins the part’s surface finish, and can lead to catastrophic tool failure.

- Work Hardening: Titanium has a tendency to harden when it is worked or machined. If your cutting tool is slightly dull or your feed rate is too low, the tool can rub against the surface instead of cutting it, creating a hardened layer that is even more difficult to machine on the next pass.

- Chip Control: The chips produced when machining titanium are often long, stringy, and tough. They don’t break easily. These "bird’s nests" can wrap around the tool and workpiece, leading to tool breakage or scratching the finished surface. This is a particularly serious problem in grooving, where there is limited space for chips to escape.

These challenges are why a simple 10-minute operation in aluminum might take an hour in titanium and require three different cutting tools. It demands a different approach, specialized tooling, and a deep understanding of the material’s behavior.

Conclusion

Mastering titanium involves understanding its strengths and weaknesses. By using the right tools, speeds, and coolant strategies, you can overcome its machining challenges to produce exceptional aerospace parts.